Today—Sunday 18 September—we commemorate the extraordinary life of Dag Hammarskjöld (1905–1961), diplomat, economist and author, killed on a ceasefire mission to the newly independent Congo.

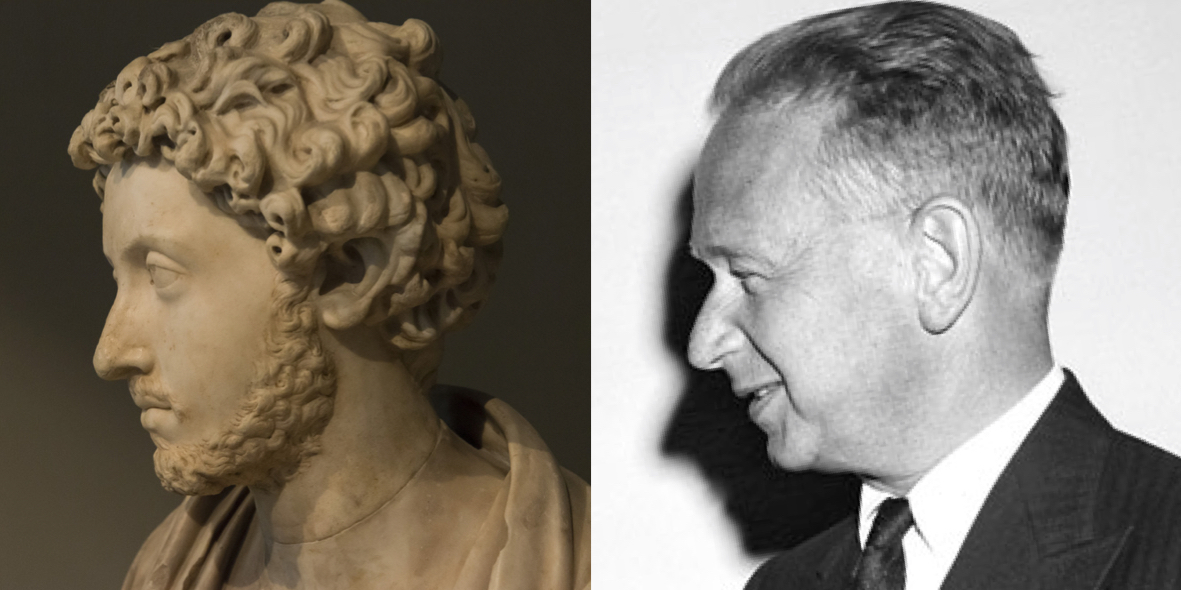

Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary General of the United Nations, photographed in 1959. This picture appeared in the Guardian on 19 September 1961, the day after his fatal plane accident. Courtesy of MPI/Getty Images.

Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary General of the United Nations, photographed in 1959. This picture appeared in the Guardian on 19 September 1961, the day after his fatal plane accident. Courtesy of MPI/Getty Images.

“Around a man who has been pushed into the limelight, a legend begins to grow as it does around a dead man. But a dead man is in no danger of yielding to the temptation to nourish his legend, or accept its picture as reality. I pity the man who falls in love with his image as it is drawn by public opinion during the honeymoon of publicity.”

Dag Hammarskjöld, Markings, 1963.

No honeymoon lasts half a century. Now, fifty years later, Dag Hammarskjöld is still the focus of publicity, albeit as the victim of a Cold War conspiracy. Nevertheless, he survives in our memory and is remembered today, 18 September, by countless people around the world. It is as if we can’t let go of the event or, more importantly, of the man himself. However, most people are preoccupied by his death rather than with his life; by his grim murder rather than his greatness as a modern, forward-looking individual.

Marcus Aurelius

Death comes to us all, Hammarskjöld knew, but not necessarily at the time of our own choosing: “Do not seek death. Death will find you,” he reflected in his still unpublished diary, Markings. Two thousand years earlier, Rome’s wisest emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote virtually the same lines in his Meditations: “It is not death that a man should fear. You will meet it.”

Both leaders were men of action and contemplation and kept a diary for their own self-improvement, addressing it ‘To Myself’. Both works are monuments to the principles of civil service and duty, and were published posthumously. Both men shared one desire: to be a wise and just philosopher-king. Both men shared a common greatness.

Marcus Aurelius c.180CE and Dag Hammarskjöld 1959. Courtesy Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Venezia and UN Photo Archives.

Marcus Aurelius c.180CE and Dag Hammarskjöld 1959. Courtesy Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Venezia and UN Photo Archives.

As we have seen in Knot of Stone (KoS pp.308-312), great men course through history like an ocean wave toward some as yet unknown shore. Some men seem not to find their way, like Alexander on the endless Asian steppe. Others get lost, as did Columbus on the unknown Atlantic. But truly great men give momentum and direction to an entire epoch.

Dag Hammarskjöld was one such great man. Following his death, John F Kennedy said apologetically: “I realise now that in comparison to him, I am a small man. He was the greatest statesman of our century.” Hammarskjöld had set a benchmark for great leaders. With the publication of Susan Williams and Göran Björkdahl’s new-found evidence (Guardian, 17 August 2011), there may yet be more to say about his death.

But let’s not dwell on Hammarskjöld’s plane crash—whether by accident or design—or give any credit to allegations that he was shot by Theunis Swanepoel, aka Rooi Rus (Red Russian), a former South African sabotage squad member. Archbishop Desmond Tutu put this tragic matter to rest during his media briefing for the SA Truth and Reconciliation Commission on 19 August 1998. Perhaps we should let sleeping dogs lie. At least for now.

In the final analysis it doesn’t matter who gave the order or who shot the fatal bullet. Instead we should ask what Hammarskjöld achieved with his life and what he managed to fulfill before he died? Just before his death he’d written to himself: “Do not seek death. Death will find you. But seek the road which makes death a fulfillment.”

Hammarskjöld wanted Africa to have its second chance after colonisation. He wanted Africans to shape their own destiny, eventually. Europe had been through this process itself, three-or-four times before, ever since Attila the Hun came storming through.

He wanted to give Africa its heart back or, rather, to prevent Congo from being plucked in two. By 1960 the continent had become the great rift valley of the world, divided on the one hand by America and Russia, and on the other by the British, French and Belgians. Sometimes by them all. More than anything else, Hammarskjöld wanted stability, security, and freedom from fear, as well as an end to the Cold War in Africa. In short, world peace and universal order. Plus more silence and time to meditate himself.

But the ocean swell had picked him up and so he rose with it. Already in the 1950s, Hammarskjöld had intervened to settle conflicts around the Suez Canal, then a faultline between the West and the East. He also tried to stabilise matters between Israel and the Arab states.

A decade earlier, around 1947–48, Hammarskjöld played his part in the recovery of post-war Europe, helping the Marshall Plan keep capitalism and communism on separate sides of the Iron Curtain. The West brewed coffee, the East boiled tea while Hammarskjöld drank both, often alone, sadly.

Gustavus Adolphus

John F Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev shared a dislike for Hammarskjöld’s initiatives; for his ability to shape events beyond their reach. This was not new, of course, as world powers have never liked a Swede with attitude. Remember what happened to Gustavus Adolphus, the celebrated king of Sweden during the Thirty Years War? He resisted the Habsburgs and the conquering Catholics in Europe—and was eventually killed doing so. (KoS p.312) As Adolphus treated Vienna and Rome, so Hammarskjöld handled Moscow and Washington. He wouldn’t bow to either.

Curiously, Adolphus and Hammarskjöld share many attributes, both in life and death. They both died with the grass in their hands and, allegedly, a wound to the head. If these allegations are proven true, then both men may have been executed.

Portraits of Dag Hammarskjöld (1905-1961), Gustavus Adolphus (1594-1632) and Charlemagne (c.742-814).

Portraits of Dag Hammarskjöld (1905-1961), Gustavus Adolphus (1594-1632) and Charlemagne (c.742-814).

However, beside their remarkable physical likeness, these two men saw themselves as representing the interests of both the nation and the individual; of the ruling elite as well as the common man: “I am born to live and die for the common good and well-being of my people. My destiny is knotted into theirs.” (Adolphus, Coronation speech, 1617).

Charlemagne

Hammarskjöld too was a man who bound rulers to their citizens and, like Charlemagne, wove their desitiny into a single inseparable knot. Charlemagne not only united the isolated peoples of Europe, albeit brutally, but also stabilised East-West relations in a medieval world. Likewise, Hammarskjöld strove for this in a modern context and today his legacy survives through the Council of Europe. Uncannily, legend has it that both men were found seated after death and in possession of a book. Moreover, by some unusual coincidence, Dag Hammarskjöld’s three middle names are phonetically similar to that of Charlemagne = Carl Hjalmar Agne.

Be that as it may, on 24 August 1961, a mere three weeks before his death, Hammarskjöld made his last entry in Markings. As usual, it was a poem. The first stanza reads:

Is this a new land,

in a different reality

from today’s?

Or have I lived there,

before this day?

However brief, Hammarskjöld’s final words echo those immortalised by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in Sudden Light, 1863:

I have been here before

But when or how I cannot tell;

I know the grass beyond my door,

The sweet keen smell,

The sight, the sound, the lights around the shore.

As a man of action and contemplation, Hammarskjöld pursued the Platonist ideal of a wise and just philosopher-king. He may not have been a ruler, or even “the greatest statesman of our century”, but he was essentially a leader and a philosopher. A great man, nevertheless. (KoS p.344)

Why mention him on this blog? Firstly, Hammarskjöld died 50 years ago, Almeida 500 years further back in history. Both deaths are shrouded in mystery and intrigue. Moreover, both men play an important role in unravelling Knot of Stone.

Nicolaas Vergunst

Le Mont Sainte-Odile in winter, with the lights of Strasbourg on the horizon. Photograph by Jean Isenmann.

Le Mont Sainte-Odile in winter, with the lights of Strasbourg on the horizon. Photograph by Jean Isenmann. Ruins of Abbaye de Niedermunster. The crypt has long since disappeared. Photograph by Martine and Ralph.

Ruins of Abbaye de Niedermunster. The crypt has long since disappeared. Photograph by Martine and Ralph.