De ruimtevaarder (spaceman) is a typical travel ballad by singer-songwriter Stef Bos, appearing on his 2005 album Ruimtevaarder. Once a borderless roamer, the renown Dutch troubadour now lives in Cape Town. Music courtesy of Niemandsland.

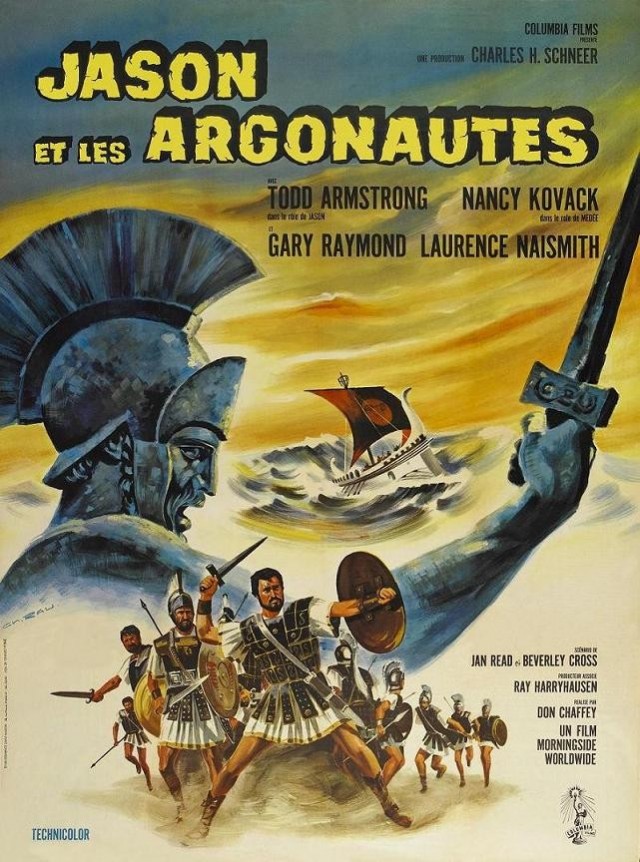

“Both Jason the Argonaut and Henry the Navigator sent their seafarers to the ends of the world and did what others thought impossible: they made the promise of a safe return a reality.” Volodya Vasilevsky, KoS p.246

Among the many parallels in Knot of Stone is the comparison between ancient mariners and modern explorers. We begin this month’s post with an extract from the book:

‘The legend of the Golden Fleece is based on voyages made around 1500BCE, when seaborne gold-prospectors crossed the Black Sea,’ said Volodya, ‘although the story’s origins date back far further.’

→‘Dating back to a distant pre-Christian Georgia?’→

→‘Yes, where they washed their alluvial sediments through a sheep’s skin, trapping the grit in its fatty curls. So, voilà, the legend is partly true… at least one part is history, the other allegory.’

→‘Allegory? Why, because the argonauts were like astronauts?’

→’‘Précisément, bon. Yes, both possessed courage, both undertook voyages into the unknown and went beyond their respective horizons—’

→‘—as had Dias,’ she said, testingly, ‘going to the Back o’ Beyond?’

→‘Yes, that’s why they nicknamed him the “Captain of the End”.’

→‘Who, Dias?’

→‘Da, because he brought his men back from the End-of-the-Earth, from Ultima Thule, whose limit was yet unguessed.’

→‘Well, I can’t leave home without a TomTom.’ He seemed not to share her humour. ‘Sorry Volodya, please continue.’

→‘Merci. There are some obvious parallels between the founding of an ancient Greek state and the emergence of the Portuguese nation: Jason and Henrique were both princes who sent seafarers to the ends of the world and did what others thought impossible: they made the promise of return a reality—’

→‘—but Prince Henry never sailed so far himself.’

→‘—but Prince Henry never sailed so far himself.’

‘No, indeed, but that made him no less adventurous. Since Antiquity the southern hemisphere was believed to lead to the Underworld—the World’s End—where the natural order was reversed.’

→Pulling herself back, she heard Volodya explaining how the voyage of the Argo symbolised a descent into the Underworld—a world of initiation.

→‘I thought we were talking about Prince Henry?’

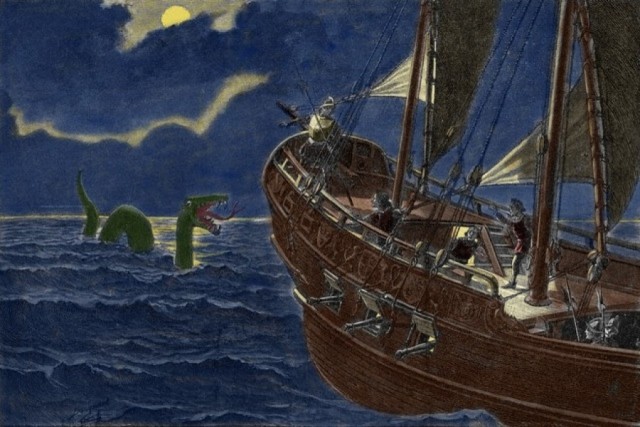

→‘Da. His navigators had to face terrible sea monsters and, like the dragonslayers of yore, had to vanquish the unknown.’ (KoS pp.246-247)

Early explorers were taught to face fearsome creatures at sea and, like their modern counterparts in space, learnt to overcome the fear of an alien-inhabited world or universe. Follow our discussion on facebook with Nicolaas Vergunst.

Early explorers were taught to face fearsome creatures at sea and, like their modern counterparts in space, learnt to overcome the fear of an alien-inhabited world or universe. Follow our discussion on facebook with Nicolaas Vergunst.

Prince Henry and King John

When Henry the Navigator died in 1460, aged 66, his nineteen year old grandnephew João was made responsible for exploring the seemingly endless Atlantic-African coastline. Little progress was made, however, until the Crown Prince became king and resumed Henry’s quest for a sea passage to the Indies.

When Henry the Navigator died in 1460, aged 66, his nineteen year old grandnephew João was made responsible for exploring the seemingly endless Atlantic-African coastline. Little progress was made, however, until the Crown Prince became king and resumed Henry’s quest for a sea passage to the Indies.

Despite claims to the contrary, young king João was optimistic that the great geographer-astronomer of Antiquity, Ptolemy, had been mistaken when he said the Indian Ocean was a landlocked “Emerald Sea” and, moreover, that Africa and India were connected by a bridge of land. Like his grand-uncle Henry, João held to the classical idea of a Great Outer Sea surrounding the world. Greek and Arab geographers had seen this as a vast river; encircling all Europe, Asia and Africa. Like  Henry, João believed the Indian and Atlantic met below Africa, and by the mid-1480s felt that the terminal point lay within his reach. (KoS p.92)

Henry, João believed the Indian and Atlantic met below Africa, and by the mid-1480s felt that the terminal point lay within his reach. (KoS p.92)

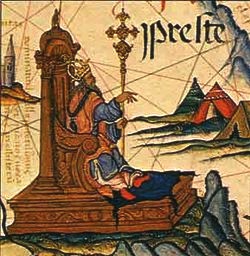

To this end king João elected Bartolomeu Dias, a schooled mariner and minor noble, to sail around Africa’s southern extremity. Dias was told to secure a sea route around the Muslim trade monopoly of the Mediterranean—and to locate the legendary Prester John, a Christian priest-king reputedly living in the Indies (then known as India, Libya or Abyssinia, see KoS p.175). In 1487, the same year Dias set sail, Pêro da Covilhã was sent to Cairo to espy an overland route to the Indian Ocean Rim and, likewise, to seek the paradisal realm of Prester John. As with Almeida, both Dias and Covilhã belonged to the Order of Christ; that is, to the brotherhood’s secret inner circle. (KoS p.85)

Bartolomeu Dias

Dias left with the best charts and latest equipment, commandeering two caravels and a broad-bottomed boat for extra supplies. He took a padre, three stone crosses, and four female hostages from Guinea. He was told none could be set ashore until he passed the furthest landfall made by earlier Portuguese explorers. (KoS p.95-96)

Dias left with the best charts and latest equipment, commandeering two caravels and a broad-bottomed boat for extra supplies. He took a padre, three stone crosses, and four female hostages from Guinea. He was told none could be set ashore until he passed the furthest landfall made by earlier Portuguese explorers. (KoS p.95-96)

Dias sailed down the west coast of Africa, beyond the mouth of the Congo River, ever further and further south, until, tired of beating against the wind, he set a course for the open sea. However, driven off course by a storm, he did not see the Cape, being then too far south at sea. The land ahead now lay to the other side of their ships and followed an eastward trend. It was only when he saw Table Mountain on his return, some weeks later, that he renamed it Cabo da Bõa Esperança, the Cape of Good Hope.

Hunger, fear, superstition and the threat of mutiny forced him to turn his boats and sail for home. He felt humiliated. In Lisbon he failed to receive the gifts once lavished on his predecessors. He was told, instead, to confer with the royal mapmaker, Bartolomeu Columbus—brother of Christopher Columbus—and to supervise shipbuilding for another expedition. Faster caravels would be needed for the next trip.

A decade later, demoted and disillusioned, Dias served as a pilot on Vasco da Gama’s epic voyage of 1497, but only sailed as far as the Cape Verde Islands. Then, in 1500, he sailed across the Atlantic with Cabral’s fleet,  reaching the shoulder of Brazil in the company of Gaspar das Índias, before swinging back toward the southern tip of Africa. On approaching the Cape a comet streaked the sky—a heavenly portent, they thought—after which a rogue wind sank four ships. He and his men were never seen again. Ironically, Dias died at the Stormy Cape he himself had named the Good Hope. Alas, he never found this Preste João. (KoS p.100-101)

reaching the shoulder of Brazil in the company of Gaspar das Índias, before swinging back toward the southern tip of Africa. On approaching the Cape a comet streaked the sky—a heavenly portent, they thought—after which a rogue wind sank four ships. He and his men were never seen again. Ironically, Dias died at the Stormy Cape he himself had named the Good Hope. Alas, he never found this Preste João. (KoS p.100-101)

Like the archetypal southern voyager, Ulysses, Dias floundered in sight of his goal. As did Moses. In fact, the Italians compared Dias to Moses as both were “permitted to see but not enter the Promised Land”. (KoS p.118)

Pêro da Covilhã

Covilhã was a traveller, a linguist and a negotiator extraordinaire. He was reputedly, too, “the most famous secret agent of his day”. He was sent to spy in Spain and served as ambassador in Morocco. Disguised as a Muslim trader, he left the same year as Dias by way of Alexandria, Cairo and Aden; taking a circuitous route to Cananor, Goa, Calicut and Cochin; then back via Ormuz before sailing down to Kilwa and Sofala. Here, on the far side of Africa, he hoped to meet Dias, or at least hear news of his visit. But they never saw each other again. Instead, Covilhã heard from an Arab or Hindu merchant that the sea beyond the tip of Africa lay open to the west—a fact Dias was discovering for himself, but now in reverse.  Some say it was the most important joint-venture in the history of pioneer exploration. (KoS pp.79, 156-157)

Some say it was the most important joint-venture in the history of pioneer exploration. (KoS pp.79, 156-157)

After a long and tiresome journey, Covilhã finally reached Emperor Eskender’s court in Yeha, near Axum, Ethiopia, where he was detained for the thirty years. He was well cared for and respected—but never allowed to leave court.

Despite the splendour, Covilhã found little resemblance to the legend of Prester John. As had Marco Polo two centuries before. After completing his travels in South Asia, Polo identified Praeti Jiani as one of the great Mongol Khans—with whom lived the Manichaeans and Nestorians, the so-called White Christians of China.

Three decades later, in 1520, when a new Portuguese party arrived, they found Covilhã still there with an Ethiopian wife and family. Covilhã was praised for his wit, intelligence and his role as an advisor. He died in Yeha a few years later, having never seen his wife in Lisbon nor the child she’d been carrying thirty years before. (KoS p.133) No doubt he also found his Prester John. Or his own terrestrial paradise. (KoS pp.118)

Spiritual enlightenment

An eastward voyage symbolised spiritual enlightenment. East was where the Terrestrial Paradise could be found. For this reason Portugal’s exploration from West Africa to East Africa, or from the shores of the Atlantic to the Indian seaboard, was far more than a mere adventure in maritime geography. Dias found not only the end of a continent but crossed a great divide, breaking into a new world, from a savage West to a fabulous East. And, ultimately, it was Gama who provided the proof and Camões the symbolism.

Read about the Terrestrial Paradise in our previous post on Prester John of Africa.

Nicolaas Vergunst

When Christopher Columbus was on first voyage to find India in October 1492, the ship hit the doldrums, wind died and they rocked for days in the windless sea… The men threatened to mutiny and turn back… They spied “monsters” in the depths, and Columbus used this to scare the mariners… They had been waylaid in the Sargasso Sea and believed the seaweed swishing around the ship were giant octopi, when the wind kicked up they set sail again… The mariners believed the monsters were under the ship and historians wrote of it.

I wrote an article years ago and came across this info. Also, Columbus kept two sets of logs, one for his eyes only so no one else knew the route.

A fascinating saga, Anita, thanks for sharing your research.

To emphasise history cementing the Cape’s link to Portugal, here’s a snap taken from the upper deck of the frigate NRP Álvares Cabral in 2007. I like to think of it as “Dias’s Revenge” since he, a captain in Cabral’s fleet, died off his “Cabo das Tormentas” ten years before Almeida landed.

The NRP Álvares Cabral was part of a visiting NATO fleet, the flagship of which was the USS Normandy, en route to do the work of Empire at the time.

The visiting frigate NRP Álvares Cabral (your photo is not visible here) lies near the spot where we think Dias and Almeida first came ashore: Dias with an astrolabe to calculate his latitude, Almeida with a carafe of wine for his lunch. Ironically, both died trying to round the Cape. Cabral, however, was first to set foot in America, Africa and Asia, thus binding together four continents in the name of the largest maritime Empire the world had ever seen. Mike, you’ll find their biographies in KoS pp.79-80.