The story behind Knot of Stone begins in June—yes, that’s this month—following the arrival of Sonja Haas in Cape Town. To assist our new readers, we’ve compiled a chapter summary of Sonja’s journey and will, day by day, add highlights from her trip. So, watch this space…

Chapter 1: lower contour path, Table Mountain, Cape Town.

Sonja Haas (35), a visiting Dutch historian, and her mentor Prof Mendle (65), sit beside a mountain stream above Cape Town. They discuss old burial customs, slavery, and the forgotten outcasts of Robben Island—mutineering sailors, convicts and lepers—until an urgent phone call cuts him short. As chief anthropologist at the SA Museum, Mendle is required to help examine a mass-grave exposed by a tempestuous storm the previous night. Several skeletons have been found, he is told, lying on their backs with their arms folded. More importantly, the skeletons appear to predate any foreigners at the Cape.

Chapter 2: disused railway yard, Old Woodstock Beach, Cape Town.

Mendle takes Sonja to the excavation site where she meets Jason Tomas (28), also from the SA Museum. He shows them the sand-packed bones; including clasps, buckles, riveted plates and a rusty rapier—evidence of the first fatal skirmish with European soldiers in southern Africa? So as to conduct a proper investigation, and avoid unwanted publicity, one skeleton is covertly removed and taken to the museum.

Chapter 3: anthropology laboratory, SA Museum, Cape Town.

Mendle reveals the articulated skeleton of a mature male, about sixty years of age, with a fractured skull. It has missing teeth and a severely scarred jawbone—as if struck under the chin by a double-edged blade, probably made of steel. Suspecting that they may have found the burial site of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, killed at the Cape in 1510, Mendle decides to pursue his investigation behind closed doors. However, as museum policy bars the storage of illicit human remains, he asks Sonja and Jason to swear an oath of secrecy—until the victim is identified. It’s an oath that will change their lives.

Chapter 4: military museum, Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town.

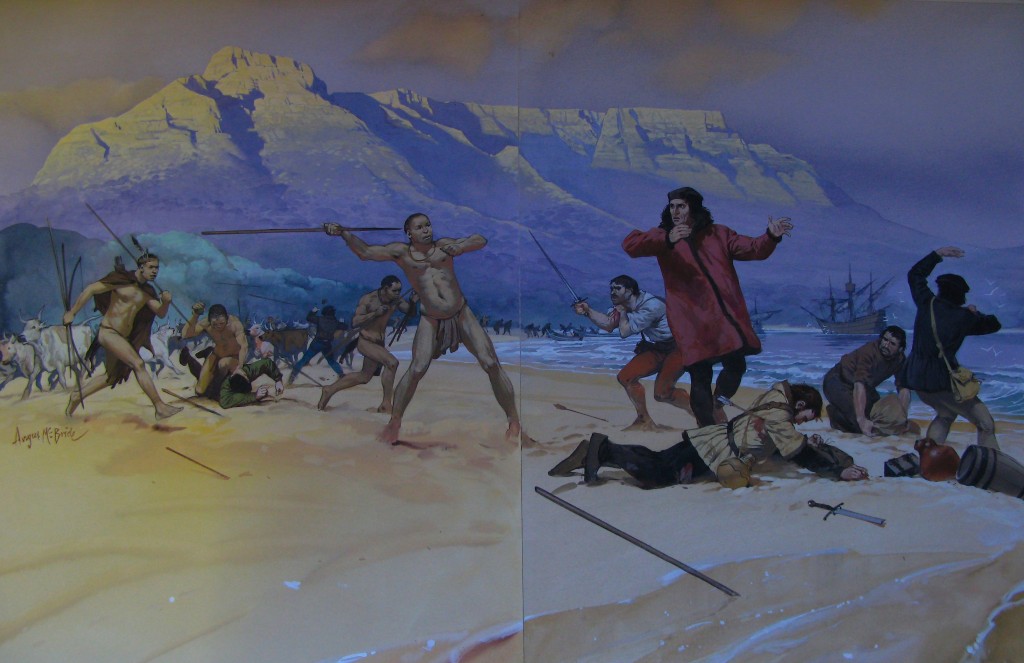

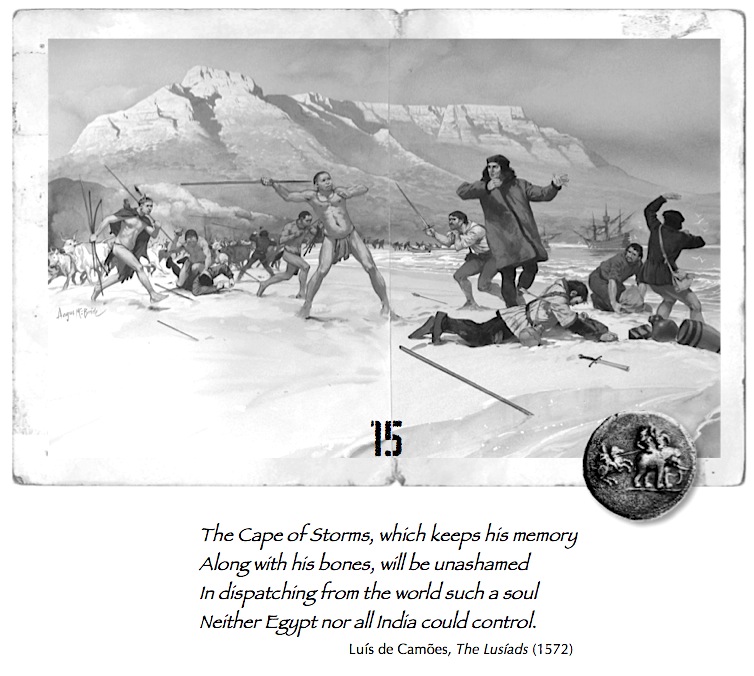

Following Mendle’s suggestion, Sonja and Jason visit the Castle Military Museum to view the only known painting of Almeida’s ill-fated death. It depicts how he and his men were ambushed by herders and stampeding war-oxen after they raided a Khoena village near modern-day Mowbray. Questioning the reconstructed facts, they search the library upstairs for more clues.

Chapter 5: military library, Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town.

Browsing between the bookshelves, Sonja and Jason learn that Almeida served both Portugal and Spain, then at war with each other, at a time when the new Discoveries of the world were being divided between the two competing sovereigns. Turning to leave, Sonja stumbles upon a dossier of scrap notes, maps and lists about Almeida’s death; including how his demise had been foretold by the so-called witches of Cochin. However irrational, or criminal, Sonja steals the dossier.

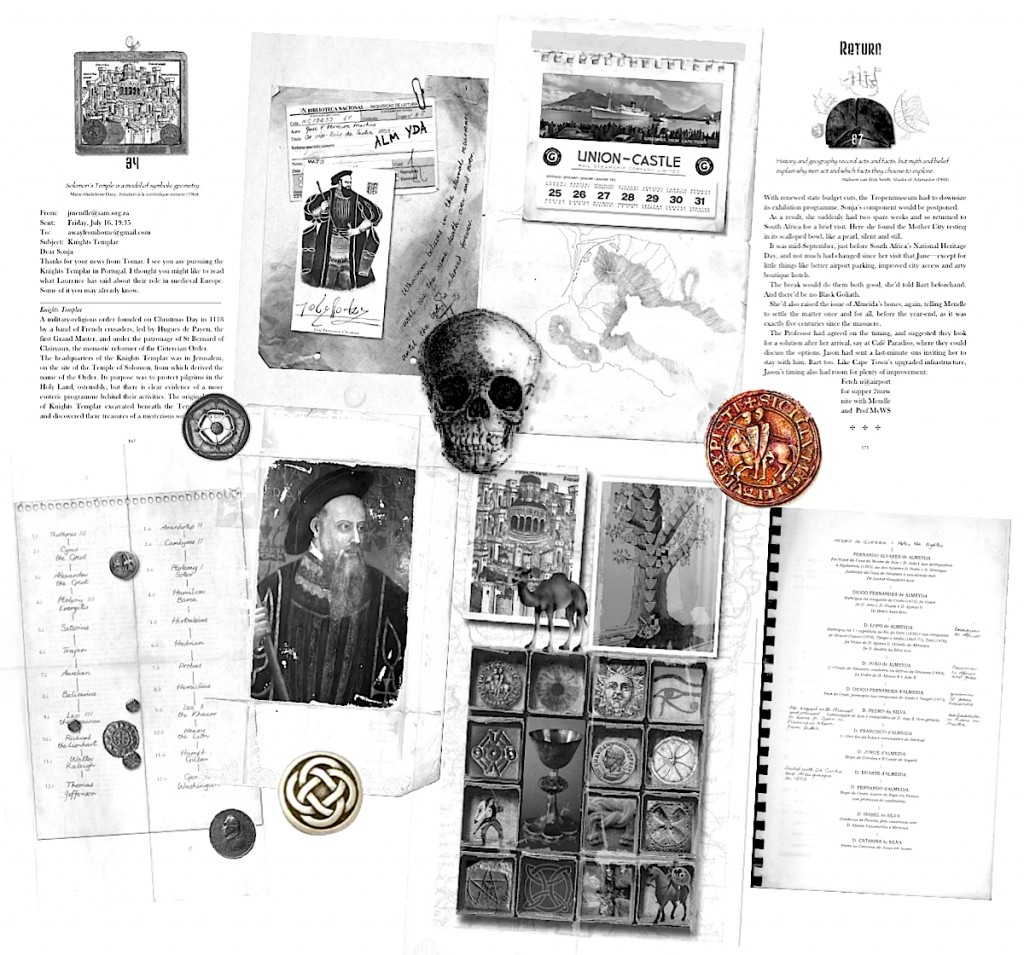

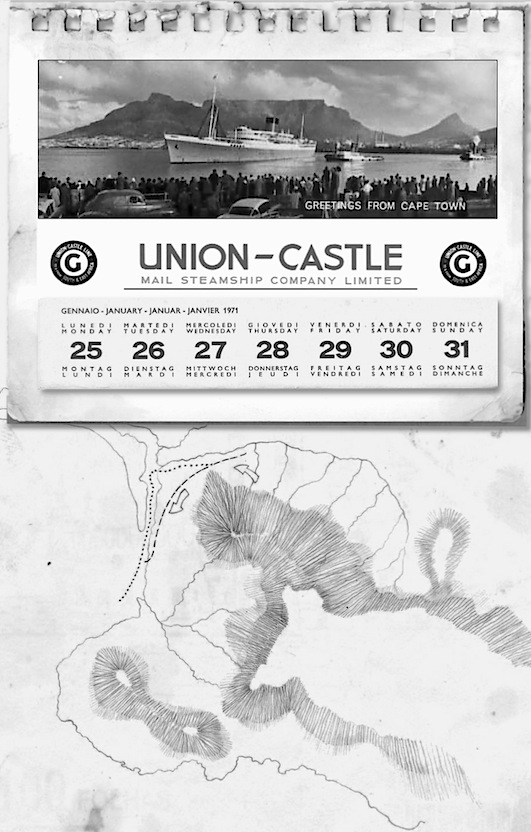

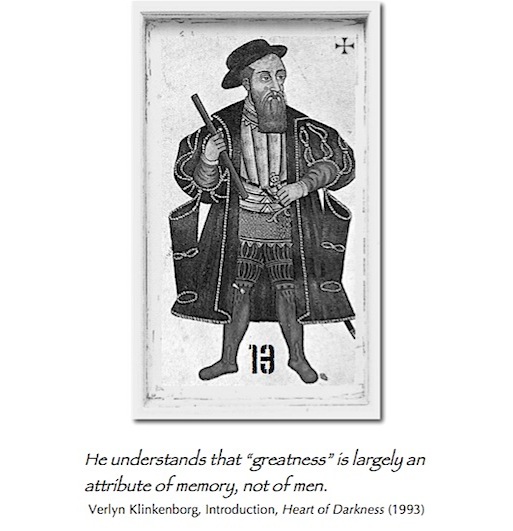

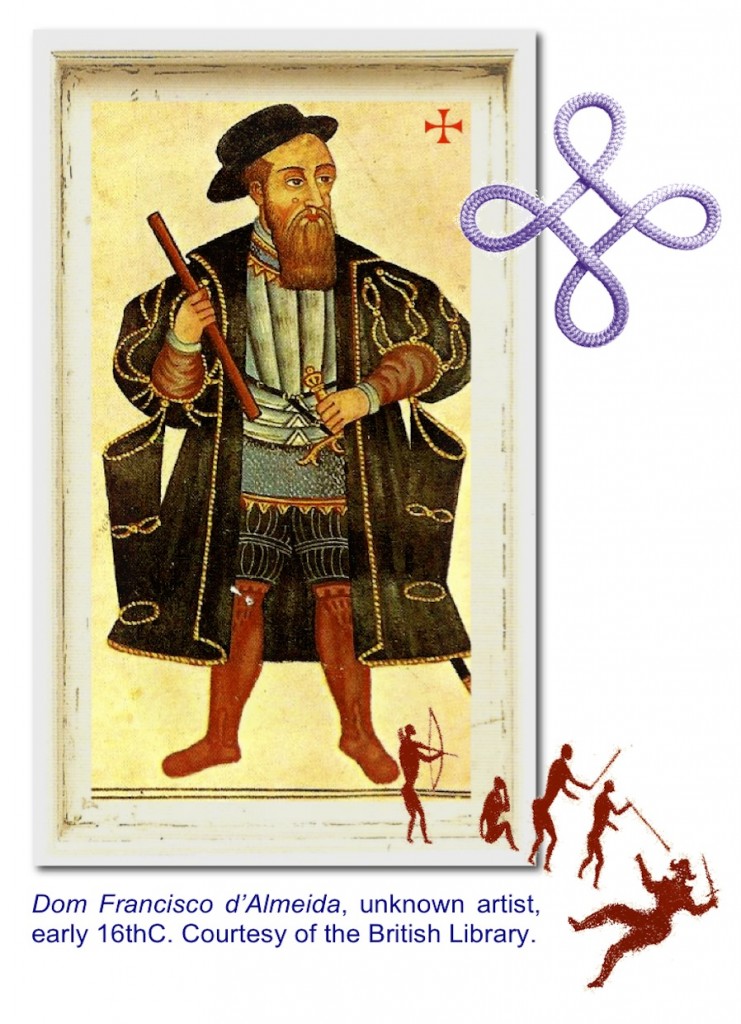

Sample pages from Knot of Stone, including items found in the stolen dossier.

Chapter 6: at home with Prof Mendle, Gardens, Cape Town.

Sonja and Jason rush across town to show Prof Mendle the dossier, asking him to explain the uncanny prediction. He cautiously notes that the prophecy only appeared after the massacre and, moreover, blends fact and fiction, history and allegory. However, Mendle quickly adds, a local clairaudient and close friend believes Almeida’s death was disguised by the Portuguese as a prophecy of doom: Almeida’s assassins ritually pierced his throat with a lance of steel, thus silencing him forever.

Chapter 7: Wild Fig Restaurant, Mowbray (below Table Mountain).

Prof Mendle and Jason join Sonja at a restaurant situated near the site of the Khoena village, now long since disappeared. Over dinner they discuss the original watering place of the Portuguese and the course of the Camissa stream. Today it flows below the city, around the Castle and under the railway line until, another mile farther, it finally flows out to sea. The stream is seen as the first “source” of modern history in South Africa. Mendle recognizes a drawing of Table Mountain’s environs, including the Camissa, shown beneath a Union Castle Line calendar. The map only makes sense when turned sideways. What then of the skull, should he have turned that too? Was Almeida struck by someone standing over his body, after he’d fallen to the ground? And since a steel blade was used, could one of his compatriots have wielded it against him?

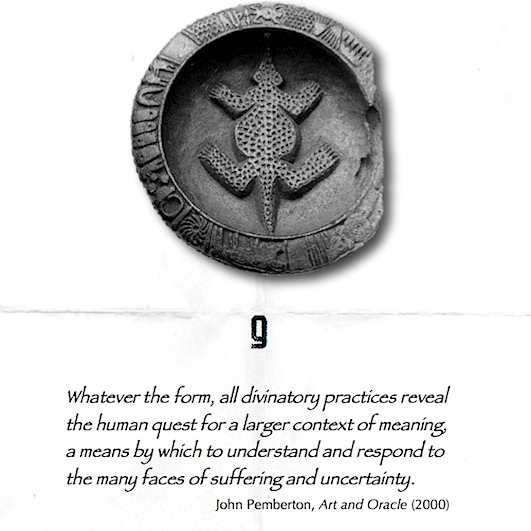

Chapter 9: apartment in Queen Victoria Street, Gardens, Cape Town.

African divination bowls or baskets—shown below with diverse bones, shells, nuts, buttons and coins—are used to determine guilt or innocence. Having seen such artifacts at the SA Museum, including one that can identify liars, Sonja wonders if these may help reveal Almeida’s assassins? However, she quickly dismisses the idea as too fanciful and far-fetched: “I’m not going to become a cultural tourist in ancestral Africa.” (KoS p.47)

Photographs courtesy of the Science Museum of London (L), and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (R).

Photographs courtesy of the Science Museum of London (L), and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (R).

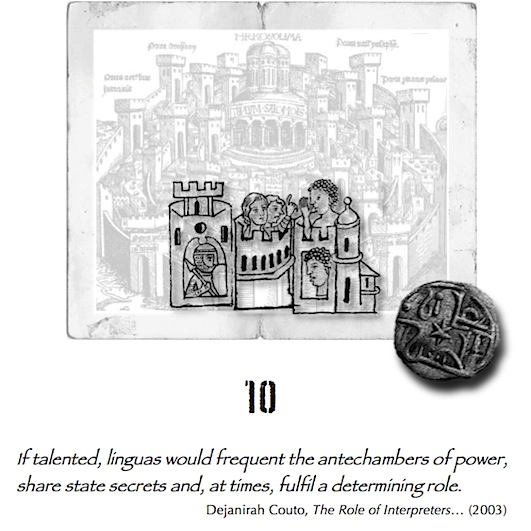

Chapter 10: museum café, SA Museum, Cape Town.

Sonja checks the clairaudient message, noting that Almeida had been sent to Cochin, India, with a “secret commission to reopen channels of esoteric intercourse between East and West”. According to the sangoma, Gaspar das Indias was privy to Almeida’s esoteric concerns and to his fear of entrapment. It seems only Gaspar knew of his master’s fate and misfortune. Sonja searches for biographical clues and learns that Gaspar’s role as lingua allowed him to move between Jewish, Muslim and Christian societies—a role that gave Almeida access to the arcane knowledge of the East.

Chapter 12: reading room, SA Library, Cape Town.

Sonja and Jason visit the SA Library to search for a motive and cause behind Almeida’s murder. They read about his term of office in Cochin and how his rival and successor, Afonso d’Albuquerque, led an abortive siege of Ormuz at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. After temporarily seizing the port, Albuquerque’s captains deserted him and sought the Viceroy’s protection back in India. Were these captains among the twelve officers killed with Almeida at the Cape?

Chapter 13: apartment in Queen Victoria Street, Gardens (below Table Mountain).

Jason sends Sonja the results of a quick internet search—Almeida’s portrait and a brief biographical synopsis. He is shown with a wart on his cheek. The striking resemblance confirms that the cards and stamps found in the dossier belong to Almeida too. It is clear that Almeida fell out of favor with Manuel I back in Lisbon; whereas Albuquerque, boldly seizing strategic territories in the Indian Ocean, won the sovereign’s approval. Sonja now learns that Almeida refused to recognize Albuquerque’s credentials and had his old rival and, now, successor-in-waiting thrown in prison.

Today the work is attributed to Pedro Barretti de Resende, former secretary to the viceroy of the Estado da Índia, and the date given as 1646. The work is now in the British Library, London. (MS Sloane 197 fol. 9)

Chapter 15: artist’s studio, Wynberg (behind Table Mountain).

Intent on learning more about Almeida’s murder, and the painting she’d seen at the Castle, Sonja visits the artist in his studio. Angus McBride, however, cannot remember his painting of the massacre. Sonja jolts his memory with the mention of Almeida’s rival and successor, Albuquerque. The artist recalls the aborted siege of Ormuz and how Albuquerque appropriated the captains’ share of the booty. More over, he says, Almeida never questioned the captains for their desertion, but took their word on trust. Angus describes Albuquerque’s illness and death, and how his bones could not be returned to Portugal as long as king Manuel I lived. Likewise, she realizes, “Almeida’s bones protect the Cape”. Was there more to the prophecy of Camões, after all?

‘Massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, 1510’ by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy Castle Military Museum.

‘Massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, 1510’ by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy Castle Military Museum.

Chapter 16: Milnerton Beach (opposite Table Mountain).

Sonja and Prof Mendle take a stroll on Milnerton Beach at low tide. According to Camões, Almeida was killed in retribution for his actions in East Africa—especially Kilwa and Mombasa—while the witches’ prophecy claims that the Cape of Storms is destined to preserve Almeida’s memory with his bones. Besides Almeida and Gaspar das Indias, Sonja cannot trace the other victims of the massacre, and so Mendle suggests she look at who did survive instead. They are listed in the dossier, he says, and most likely named for a good reason. She now knows that Almeida, like Gaspar, was a special envoy who mixed with monarchs, diplomats and well-travelled scholars; and thereby acquired the arcane knowledge of Asian cultures.

Chapter 20: maritime museum, Mossel Bay, Garden Route.

With only a week left to complete her research in South Africa, Sonja drives up the Garden Route to visit the Dias Museum. The maritime museum stands beside a perennial spring where Bartolomeu Dias made his historic landing, the first along these shores, in 1488. The site also marks the first encounter and earliest recorded death in South Africa. Here, at the spring, an affronted herdsman was shot in the throat by a Portuguese crossbow bolt. Two decades later, beside another stream, this time at the Cape of Good Hope, Almeida would die with a wooden spear stuck through his throat too.

Chapter 21: museum café, SA Museum, Cape Town.

Sonja tells Prof Mendle about her trip to the Dias Museum and the confusions caused by unreliable historical sources. He uses Aristotle’s distinction between history and poetry to demonstrate that history merely shows us who we once were; whereas poetry shows who we are—or could still be—inspiring us to strive for something far greater. Most historians believed it was their duty to ennoble others through poetics and, like Camões, their works influenced western historical writing for two millennia—until well into the twentieth century itself.

Façade of the SA Museum, Cape Town, with the illuminated shop-café to the right of the main entrance.

Façade of the SA Museum, Cape Town, with the illuminated shop-café to the right of the main entrance.

Chapter 24: apartment in Queen Victoria Street, Gardens, Cape Town.

Before leaving Cape Town, Sonja invites Mendle and Jason for a home-made farewell dinner: an Indonesian ‘rijsttafel’. They discuss changing European perspectives of the Cape landscape and the notion that the ‘Native’ belonged to two stereotypical worlds: one where life was pastoral, tribal and stagnant; the other where life was nasty, brutish and short. Mendle points out that, while some things are new, all things in Africa are extreme.

“Out of Africa always something new.” Pliny the Elder, 23-79CE

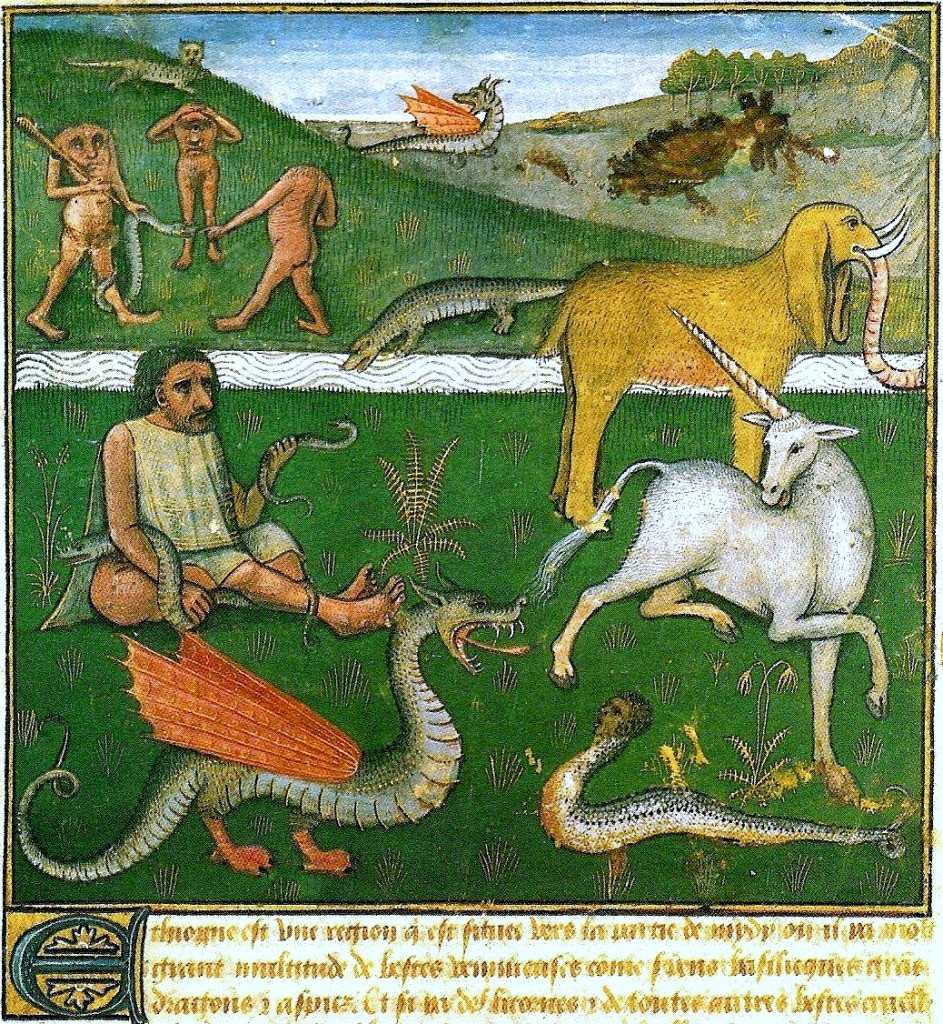

From a European perspective, Africa was invented before it was explored. By 1450, based on the geography of ancient historians, most Christians still believed Africa was divided into a savage West and a fabulous East. This single idea so possessed Prince Henry and his Navigators—then exploring Atlantic-Africa—that it transformed their Discoveries into a quest for individual spiritual enlightenment. Thus the Cape of Good Hope became a threshold on the North-South axis; and the portal between a modern West and an ancient East. In time the Cape itself, or more specifically Table Mountain, came to be seen as the biblical/mythological Terrestrial Paradise.

The fabled Aethiopes beside the Nile, source of the Terrestrial Paradise? From ‘The Wonders of the World’, 1488. Curiously, it was painted the same year Dias rounded the Cape. Courtesy Bibliothèque national, Paris.

The fabled Aethiopes beside the Nile, source of the Terrestrial Paradise? From ‘The Wonders of the World’, 1488. Curiously, it was painted the same year Dias rounded the Cape. Courtesy Bibliothèque national, Paris.

Our next blog follows Sonja as she travels across Europe—from Portugal to Holland—visiting old churches, museums and archives on her way. To preview, see Synopsis.

Nicolaas Vergunst

The Camissa stream is “a unique source of all beginnings and endings”. Correct! As a local heritage organisation, Reclaim Camissa believes this is the frontier of our modern nation:

Very interesting. I’ve been following your histoire of Francisco d’Almeida on Facebook.

Bon jour, Zia, enchanté! Given our mutual French connection (I currently live in Strasbourg), you may like to note that several chapters are set in Chartres, Paris, Andlau and at Le Monte Sainte-Odile. For an overview of the other countries visited, please see Storyline. Come visit us again!