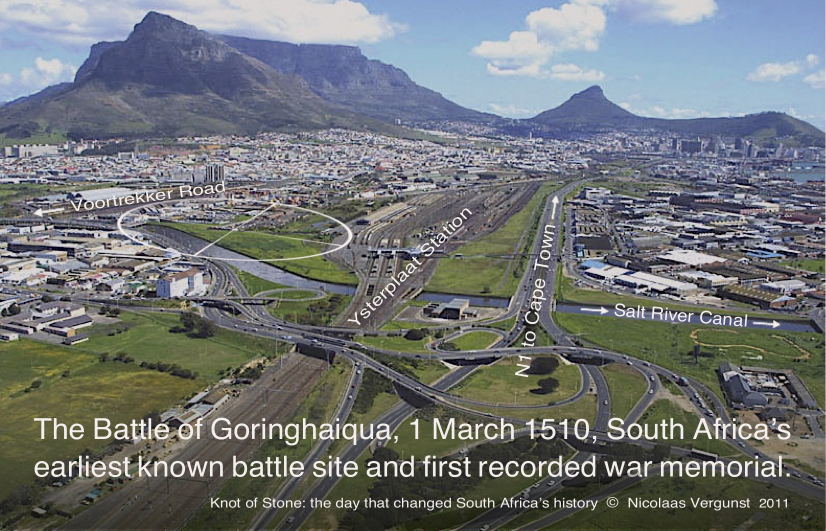

Bird’s eye view of the alleged battle-burial site (encircled), seen adjacent to the Salt River Canal and hemmed in between Voortrekker Road and Ysterplaat Station, c.2011. In 1512, two years after the massacre, a wooden cross and stone cairn were erected to mark the spot but are, alas, now either lost or destroyed.

Bird’s eye view of the alleged battle-burial site (encircled), seen adjacent to the Salt River Canal and hemmed in between Voortrekker Road and Ysterplaat Station, c.2011. In 1512, two years after the massacre, a wooden cross and stone cairn were erected to mark the spot but are, alas, now either lost or destroyed.

Those following our posts will know that we have tracked the last days of Viceroy D’Almeida and may be as surprised as we are by the ‘rediscovery’ of his burial site. Here we present an overview of our latest research.

The prophecy

On leaving India in the closing months of 1509, a woman sorcerer (seer or diviner) warned the disgraced ex-Viceroy that he would not pass beyond the Cape of Good

On leaving India in the closing months of 1509, a woman sorcerer (seer or diviner) warned the disgraced ex-Viceroy that he would not pass beyond the Cape of Good

Hope—this being the western limit of his realm. Portugal’s Estado da Índia then spanned an entire ocean, stretching from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to the southern tip of India; Cape Comorin. According to the poet Luís de Camões, the sorcerers passed Almeida in a skiff as he boarded his ship, the Garça, which lay ready to leave Cochin the following day. Their prediction prompted him to rewrite his Will as soon as calmer seas permitted. Crossing the sea itself took four months (from 18 November to 20 February), and the rotting Garça sailed in stark contrast to the flagship with which he had arrived four years earlier. Unlike the twenty two that took him to Cochin—then the largest fleet ever to leave Lisbon—only two small boats now escorted him home. Rounding the Cape in fair weather, Almeida said to his attendants: “Now God be praised, the witches of Cochin are liars.” (KoS p.30)

Hope—this being the western limit of his realm. Portugal’s Estado da Índia then spanned an entire ocean, stretching from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to the southern tip of India; Cape Comorin. According to the poet Luís de Camões, the sorcerers passed Almeida in a skiff as he boarded his ship, the Garça, which lay ready to leave Cochin the following day. Their prediction prompted him to rewrite his Will as soon as calmer seas permitted. Crossing the sea itself took four months (from 18 November to 20 February), and the rotting Garça sailed in stark contrast to the flagship with which he had arrived four years earlier. Unlike the twenty two that took him to Cochin—then the largest fleet ever to leave Lisbon—only two small boats now escorted him home. Rounding the Cape in fair weather, Almeida said to his attendants: “Now God be praised, the witches of Cochin are liars.” (KoS p.30)

“God be praised, the sorcerers are liars.” Francisco d’Almeida, 1510

After sailing a few leagues farther, Almeida’s ships entered a sheltered bay where, as a welcome break from their monotony at sea, he sent his men ashore to fetch clean water and dry firewood. Here they spent the next ten days replenishing their supplies, repairing their boats and befriending local herders from whom they hoped to obtain fresh meat. Whether he was aware of it or not, one of Almeida’s officers, António de Saldanha, had watered at the same stream several years before, after which it was called the Aguada de Saldanha or Watering Place of Saldanha. The local place name was Camissa, or Place of Sweet Water, after the springs that lay nestled in the crook of Table Mountain’s arm. The mountain itself was known as Hoerikwaggo (Mountain of the Sea).

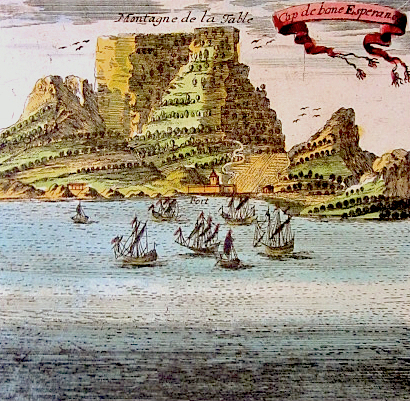

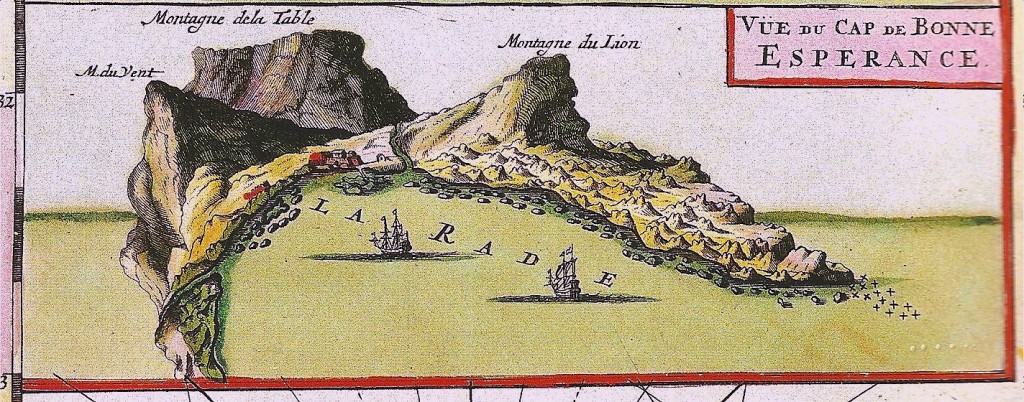

Two depictions of Table Mountain c.1680-90 show the little stream from which Almeida and António de Saldanha drew water. When they called at the Cape, in 1503 and 1510 respectively, there were no man-made structures along the beach and no other ships in the bay. The Dutch and English only began calling at the Cape in the late 1590s.

Two depictions of Table Mountain c.1680-90 show the little stream from which Almeida and António de Saldanha drew water. When they called at the Cape, in 1503 and 1510 respectively, there were no man-made structures along the beach and no other ships in the bay. The Dutch and English only began calling at the Cape in the late 1590s.

The chronicles

According to Portugal’s royal chroniclers, several curious natives came down to the beach as soon as Almeida dropped anchor (probably near today’s V&A Waterfront). Later, while his men filled their caskets and collected wood, a few brave herdsmen befriended the interlopers hoping to learn the ways of the Strange Ones. During this period Almeida yielded to requests for a party to visit a nearby village, most likely that of a Goringhaiqua clan (in the vicinity below today’s University of Cape Town), where his men claimed it was possible to barter sheep or cattle for the long journey home. When the foraging party returned, allegedly bruised and bloody-faced after a quarrel, they demanded a punitive party be sent to teach the “unpredictable” locals a lesson before the next Portuguese ships called. Reluctantly and, while suspecting foul play, Almeida agreed. (KoS p.46)

Looking with indigenous eyes, the Strange Ones were seen as coming from across the Great Water, from the nesting place of the sun. They came as birds with wings of white and swam ashore like fish with fins raised and flashing teeth. Reptile-like in scales of armour, they spat fire and attacked their prey with fierce claws of steel. They were the abeLungu.

Looking with indigenous eyes, the Strange Ones were seen as coming from across the Great Water, from the nesting place of the sun. They came as birds with wings of white and swam ashore like fish with fins raised and flashing teeth. Reptile-like in scales of armour, they spat fire and attacked their prey with fierce claws of steel. They were the abeLungu.

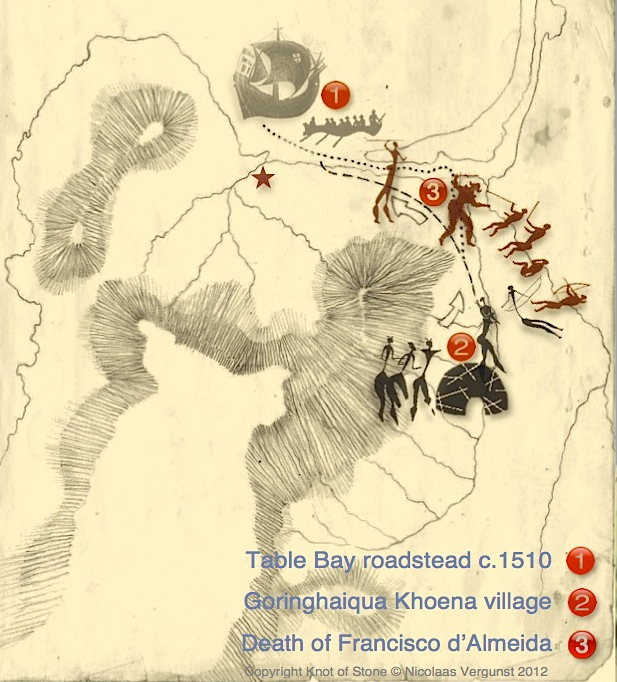

Reconstruction of the estuary where Almeida was killed (left) and its approximate location today (right). The crossed battle swords (No.3, right) mark the site along the bank of the modern canalised Liesbeeck-Salt River.

Reconstruction of the estuary where Almeida was killed (left) and its approximate location today (right). The crossed battle swords (No.3, right) mark the site along the bank of the modern canalised Liesbeeck-Salt River.

Early reconstructions

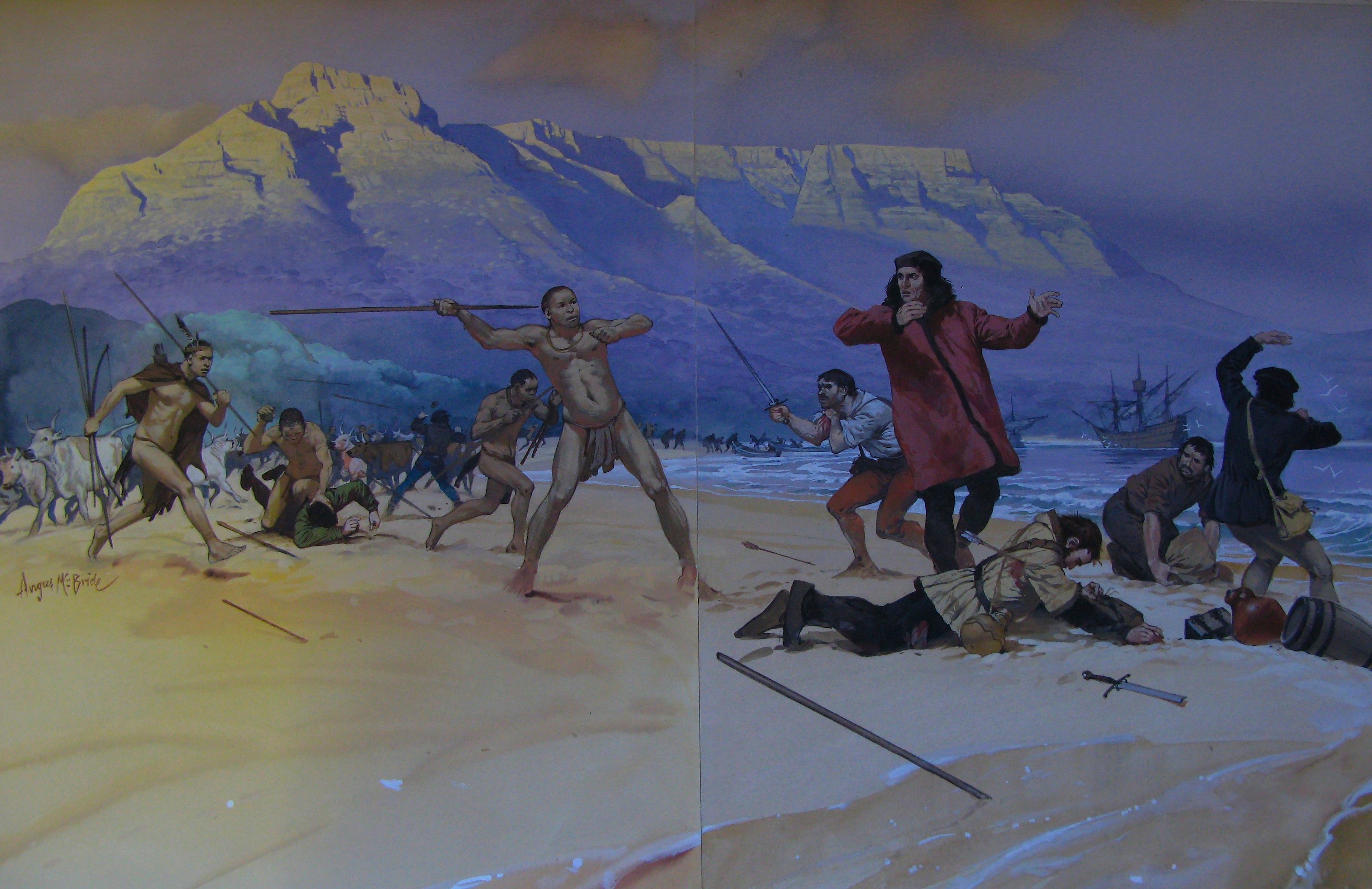

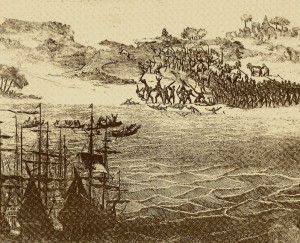

Early the next morning the Portuguese marched on the Goringhaiqua village but, before Almeida could reach it himself, some of his men broke rank to run off ahead. Finding the village deserted, the belligerent men fell upon the huts and began to pillage without constraint. In the ensuing chaos, one of the men was killed by a passing compatriot who, having heard someone rummaging within a hut, stabbed his victim through the grass-matted wall. (KoS p.81) When news of the calamity reached Almeida, still on his way, he tried to call off the expedition—but by then it was too late as the Goringhaiqua had now herded their cattle together and began to drive them on the heels of the retreating Portuguese, many of whom fell under the stampede. Those who could reach the beach, including Almeida, found themselves trapped between the rising tide and the soft dunes. Here, at the estuary of the Salt/Liesbeeck River, Almeida and his compatriots were ambushed and killed. Those who had already abandoned him—or were intent on saving themselves and their loot—fled to where the longboats awaited them. (KoS p.48)

‘Massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, 1510′ by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy Castle Military Museum.

‘Massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, 1510′ by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy Castle Military Museum.

Recent research

Despite various claims regarding the actual site—including locations in nearby Hout Bay or Saldanha Bay—the location most recently identified with the skirmish is shown below: across the Salt River Canal with Table Mountain in the background. However, since the course of the river has been redirected and tons of landfill covers the former curve of the beach, the exact site will be difficult to identify and excavate today.

While in Cape Town to commemorate the massacre of 1 March 1510, I had the rare opportunity of asking my friend Stewart Young, a polymath and gifted dowser, to help locate where Almeida met his death. With only the barest facts, Dr Young was able to detect that “the place lies under a building near an open field” and, dowsing in situ, led me from the mountain toward the shore. Unfamiliar with the terrain, we failed to see the Salt River Canal and nearby shunting yard—today covered in grass and weeds. We were also unaware of what lay behind a tall vibracrete wall that now crossed our path until, with a certain measure of surprise, Dr Young added: “Almeida fell here, and lies buried two metres beyond this wall”. Well, if that be the case, then this marks the first recorded battle site and earliest known memorial in South Africa’s history (the Portuguese erected a cairn and cross to mark the spot in 1512, two years after Almeida’s death). Hemmed in between Ysterplaat Station and Voortrekker Road today, the actual evidence lies under tons of brick and concrete. Any confirmation, albeit scientific or not, depends on further research at the site.

While in Cape Town to commemorate the massacre of 1 March 1510, I had the rare opportunity of asking my friend Stewart Young, a polymath and gifted dowser, to help locate where Almeida met his death. With only the barest facts, Dr Young was able to detect that “the place lies under a building near an open field” and, dowsing in situ, led me from the mountain toward the shore. Unfamiliar with the terrain, we failed to see the Salt River Canal and nearby shunting yard—today covered in grass and weeds. We were also unaware of what lay behind a tall vibracrete wall that now crossed our path until, with a certain measure of surprise, Dr Young added: “Almeida fell here, and lies buried two metres beyond this wall”. Well, if that be the case, then this marks the first recorded battle site and earliest known memorial in South Africa’s history (the Portuguese erected a cairn and cross to mark the spot in 1512, two years after Almeida’s death). Hemmed in between Ysterplaat Station and Voortrekker Road today, the actual evidence lies under tons of brick and concrete. Any confirmation, albeit scientific or not, depends on further research at the site.

New publication

Like most locations in my book—from ancient springs to medieval towns—the portrayal of Almeida’s final resting place is the result of several research trips spanning twenty years. The description in Chapter 2 is based on my efforts to trace the shoreline in 2007 and not, of course, on any insights made after the book was published. Despite this, the ‘new’ site presents an uncanny resemblance to the one imagined while writing Knot of Stone:

Prof Mendle set off, Sonja by his side, between piles of sleepers and tracks choked with weeds. He led her past a disused warehouse with its derelict loading bay, and then on beyond a platform strewn with splintered packing crates and old pallets. Everything was broken, barricaded and abandoned… Behind him scraps of plastic fluttered in the stiffening breeze, like the flags of a forlorn sailing ship. Beyond the barbed fence lay the Old Grey Father, Table Mountain, the ever-silent witness to many a by-gone age. (KoS p.8 and p.12)

New research has also shown that Almeida was led into an ambush by his men and that they, subsequently, reported his murder as the tragic fulfillment of the witches’ prophecy. (KoS p.33) The reasons for Almeida’s assassination will be discussed in another post.

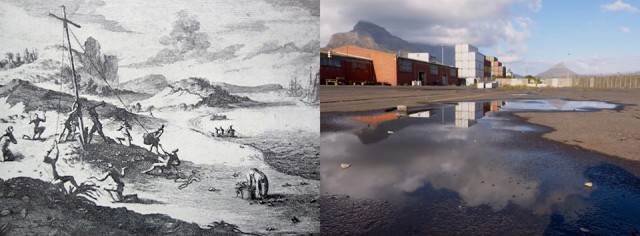

The burial site, then and now, 1512 and 2012. Unable to find the grave two years later, an ad hoc group of passing Portuguese sailors erected a stone cairn and wooden cross to mark the site. It was the first and only time that Almeida’s compatriots called again at the Cape. The engraving (left) is by Pieter van der Aa and produced for a travel book two hundred years after the event. The cross and cairn, now lost, constitutes the earliest war memorial in South Africa. The pool of water seen in the photo (right), recalls the former shoreline/intertidal zone which has also long since disappeared.

The burial site, then and now, 1512 and 2012. Unable to find the grave two years later, an ad hoc group of passing Portuguese sailors erected a stone cairn and wooden cross to mark the site. It was the first and only time that Almeida’s compatriots called again at the Cape. The engraving (left) is by Pieter van der Aa and produced for a travel book two hundred years after the event. The cross and cairn, now lost, constitutes the earliest war memorial in South Africa. The pool of water seen in the photo (right), recalls the former shoreline/intertidal zone which has also long since disappeared.

This concludes the post Earliest battle site rediscovered.

Nicolaas Vergunst

How good to see the spot where the body of Almeida rests, with Table Mountain in the background. The mountain top appears like an African headrest, shaped by bedrock for those sleeping in its shadow; or formed like an anvil to forge a new East-West history? Others say it is like an altar on which the South is united with the rest of the World?

Thanks for the comparisons, Frans, they are both poetic and iconic. As you know, Dr Zeylmans van Emmichoven described Table Mountain as an altar upon which rests the foot of the “World Cross” with its axis intersecting at Jerusalem. (read more KoS pp.241, 336)

Today, fifty years after Zeylmans himself died in Cape Town, geologists describe the North-South chain of highland mountain ranges, rift valleys and lakes as the Wall of Africa.

Position No.3 is quite different to what you photographed in Paarden Eiland; this site is somewhere in Salt River.

Bruce, the two swords mark the spot along the Liesbeeck-Salt River Canal where the N1 and M5 intersect (view an enlarged map here). The numbers themselves reveal a sequence rather than the precise position of each phase of the encounter.

Okay; I loved the map!

Helene de Villiers wrote a book called Grailstone in Africa and suggests that Francisco d’Almeida had a rare book and pearl given to him by an Arab prince at the Battle of Granada. This was meant to be passed on to the Knights of Christ, an Order to which he belonged, but he kept it for himself. The suggestion is that he was assassinated by his own people for this reason.

Thank you for sharing this information, Fiona, as it outlines an obscure tradition (usually transmitted orally) behind both Helene’s Grailstone in Africa and my Knot of Stone. As the authors of these books (mine is a novel) we each draw our information from conversations that took place in South Africa during the 1960s. These conversations were held by a select group of Dutch Antroposophists who, inspired by the early Portuguese mission in Africa, focused on the significance of Almeida’s death at the Cape. Among those involved were Helene de Villiers, Zelia Campbell, Max Stibbe, Hymen and Eva Piccard (see her citation under Reviews) and, of course, Dr Zeylmans van Emmichoven (see my response to Frans Lutters on March 3 above). According to Helene and Eva, Stibbe identified the site where Almeida was killed; though no one seems to remember exactly where it is today. Most of this group have since passed away and so, hoping to reconstruct events, I interviewed Claartje Wijnbergh-Berend for my book. As a Waldorf school teacher Claartje had worked with Zelia and Stibbe in Pretoria, staying for fifteen years, before her return in 1999 when Mandela retired. “His task was done and so was mine,” she said, “of course I had a far smaller role to play.” (see KoS pp.336-338)

While Helene and I use Walter Johannes Stein’s private notes as our primary source, Knot of Stone goes on to include both Stein’s retrospective visions and the clairaudient messages of Laurence Oliver. My reconstruction of events that fateful Friday five hundred years ago is thus based on two corroborating sources: what Dr Stein saw in 1924 and eighty years later, in 2004, what Dr Oliver heard. If you wish to read more about these two gifted men and their insights, please go to Book Review or see under Chapter 6.

Or, better still, read the Preface to Knot of Stone. I hope this background is of added value.

Hi again – I see from your reply that you are au fait with Helene’s book and will certainly keep track of your website and try to source your book. I look forward to reading it.

We are preparing an ebook version for release at the end of 2013. Meanwhile, if you’re in SA, please see our online offers at Exclusives and Red Pepper Books.