In an age of overseas exploration, c.1400-1600, modern history was born on our beaches, those marginal spaces where indigenes and interlopers first met. These encounters still shape the history, memory and identity of people today. Patric Tariq Mellet and Nicolaas Vergunst take a look at the intertidal zone of history—where local experience meets classical interpretation—and debate the first recorded skirmish on the shores of modern Cape Town.

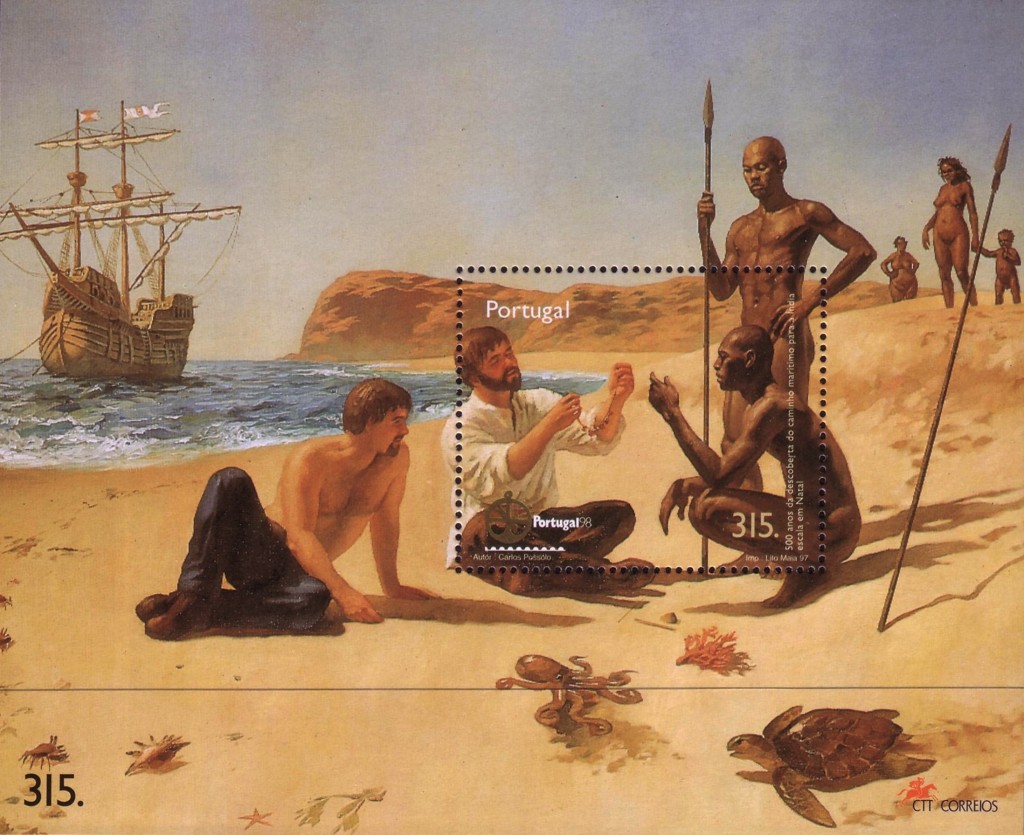

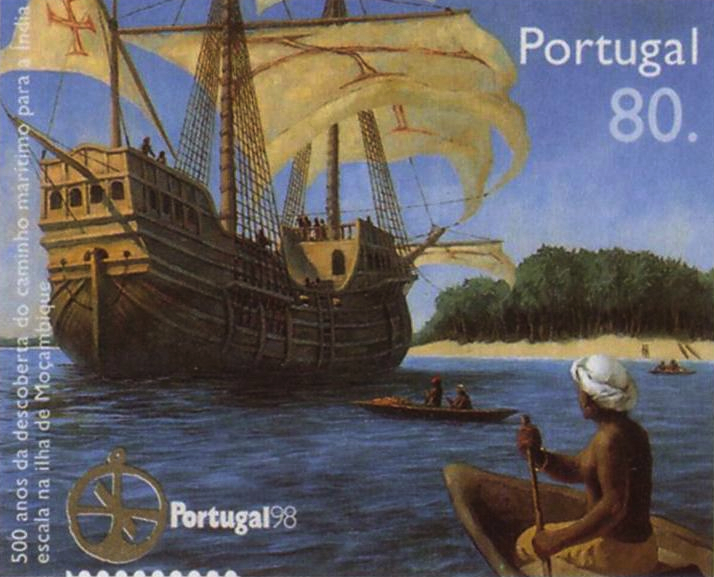

Vasco da Gama in East Africa, 1497-98, designed by Carlos Possolo. These commemorative stamps were issued in 1997 to mark the epic Portuguese voyage to India. Shown here are the beaches of Natal, Mozambique and Mombasa. Such idyllic encounters are typical of the travel books produced throughout Europe during the early decades of its overseas expansion and were, of course, read by Almeida and his contemporaries.

Patric Tariq Mellet: From the outset the Portuguese were obnoxious and aggressive. In 1510, led by Francisco d’Almeida, they came ashore and tried to steal cattle and kidnap some Khoe children. It was supposed to have been a reprisal for a clash the day before, when the Khoena had given a fellow named Gonçalo Homen a severe trashing after he tried to trick them. Almeida and his 150-200 insurgents got a severe whipping at the hands of the Khoe who were far fewer in number—an estimated 100 herders, no more. The Portuguese armour and weaponry, as well as their sheer stupidity in terms of tactics, resulted in Almeida loosing his life along with sixty-odd officers and men. The conflict on the beach illustrates two things: the hostility of the Portuguese and the determined resistance of the local Khoena to anything that smelt of exploitation and aggression.

Patric Tariq Mellet: From the outset the Portuguese were obnoxious and aggressive. In 1510, led by Francisco d’Almeida, they came ashore and tried to steal cattle and kidnap some Khoe children. It was supposed to have been a reprisal for a clash the day before, when the Khoena had given a fellow named Gonçalo Homen a severe trashing after he tried to trick them. Almeida and his 150-200 insurgents got a severe whipping at the hands of the Khoe who were far fewer in number—an estimated 100 herders, no more. The Portuguese armour and weaponry, as well as their sheer stupidity in terms of tactics, resulted in Almeida loosing his life along with sixty-odd officers and men. The conflict on the beach illustrates two things: the hostility of the Portuguese and the determined resistance of the local Khoena to anything that smelt of exploitation and aggression.

Nicolaas Vergunst: Sadly, this account of Almeida’s murder offers nothing new or even insightful, as it merely repeats the inaccuracies found in the existing historical records. For that I don’t blame you, Patric, since no one else ever stopped to question it and ask if there’d been an ambush, a mutiny or even, say, a hidden assassination from within his own ranks? It is with this question in mind that I started writing my book. In fact, whenever I heard about the tragedy it always seemed to serve two ulterior motives. First, to demonstrate the violent dangers faced by early explorers and, secondly, to show that Almeida had to pay for his arrogance.

PTM: It’s not true to say that no one else has questioned the Almeida stories as there are a number of early Portuguese writers that do; namely Barros, Castanheda, Goes and Correia. While these overlap in places, they also differ significantly too. There are also a number of British and South African versions of the story. Each seen with a different lens and, like yours, approach the story with a unique bias. I don’t see Almeida as a victim, as you say, but rather as a man who had adversaries and, like any powerful figure in history, was engaged in and/or advanced by the conflicts around him. He was a military man and an aggressor and not as incidental to conflict as you suggest. Like those who came before and after, he had powerful backers sponsoring him with their own interests. The politics of the era is interesting and not too different from today. It is certainly not a story of saints and sinners, evil and lesser evil. Emphasis on different facts takes each different bias down its own road. Perhaps if David Johnson’s excellent chapter in Imagining the Cape Colony (2012) had been available when you did your research, you’d have seen that this entire historical episode is not about ‘inaccuracies’ but all about politically charged differing versions of events and politics of the time, as well as political bias’s which continue to this day. Much of the accounts, and indeed the ‘prophecy’ itself, were written long after the fact (and indeed the prophecy being the most biased version with a nationalism agenda). What is great about Johnson’s work is that it does not carry a torch like you and I, but offers the reader differing versions, including the most recent, and allows debate to develop further based on the plurality of ‘facts’ before us. There are no ‘inaccuracies’ as such.

PTM: It’s not true to say that no one else has questioned the Almeida stories as there are a number of early Portuguese writers that do; namely Barros, Castanheda, Goes and Correia. While these overlap in places, they also differ significantly too. There are also a number of British and South African versions of the story. Each seen with a different lens and, like yours, approach the story with a unique bias. I don’t see Almeida as a victim, as you say, but rather as a man who had adversaries and, like any powerful figure in history, was engaged in and/or advanced by the conflicts around him. He was a military man and an aggressor and not as incidental to conflict as you suggest. Like those who came before and after, he had powerful backers sponsoring him with their own interests. The politics of the era is interesting and not too different from today. It is certainly not a story of saints and sinners, evil and lesser evil. Emphasis on different facts takes each different bias down its own road. Perhaps if David Johnson’s excellent chapter in Imagining the Cape Colony (2012) had been available when you did your research, you’d have seen that this entire historical episode is not about ‘inaccuracies’ but all about politically charged differing versions of events and politics of the time, as well as political bias’s which continue to this day. Much of the accounts, and indeed the ‘prophecy’ itself, were written long after the fact (and indeed the prophecy being the most biased version with a nationalism agenda). What is great about Johnson’s work is that it does not carry a torch like you and I, but offers the reader differing versions, including the most recent, and allows debate to develop further based on the plurality of ‘facts’ before us. There are no ‘inaccuracies’ as such.

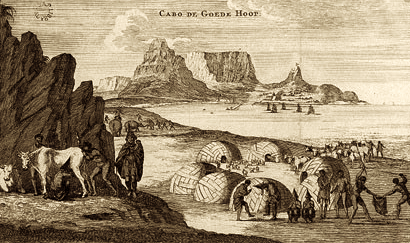

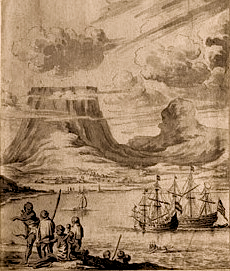

View of the Cape of Good Hope by Wilhelm Stettler, 1669, based on sketches made by a soldier-adventurer serving in the VOC, Albrecht Herport, who visited the Cape a decade earlier. While most pictures were made by engravers who never visited the Cape, this view of Table Mountain is remarkably accurate as Herport sketched it himself “naert leven” (from life). The rhinoceros, however, was copied after Albrecht Dürer’s famous Asian rhino woodcut of a hundred and fifty years earlier, 1515. While the Khoena wear the traditional sheepskin cloak (kaross) and rolled leather thongs (riems) around their legs, their bodies are composed like figures in a Greek pediment. Here fact and fantasy combine in a single work to create an ‘Arcadian Africa’. Likewise, written accounts tried to combine the same elements into a seamless historical record.

View of the Cape of Good Hope by Wilhelm Stettler, 1669, based on sketches made by a soldier-adventurer serving in the VOC, Albrecht Herport, who visited the Cape a decade earlier. While most pictures were made by engravers who never visited the Cape, this view of Table Mountain is remarkably accurate as Herport sketched it himself “naert leven” (from life). The rhinoceros, however, was copied after Albrecht Dürer’s famous Asian rhino woodcut of a hundred and fifty years earlier, 1515. While the Khoena wear the traditional sheepskin cloak (kaross) and rolled leather thongs (riems) around their legs, their bodies are composed like figures in a Greek pediment. Here fact and fantasy combine in a single work to create an ‘Arcadian Africa’. Likewise, written accounts tried to combine the same elements into a seamless historical record.

NV: I’m not talking about differing versions of the same episode. What we have here is the same overall story—one in which the event and its core structure stays the same, only certain facts are presented or omitted to promote a particular view or interest group; albeit Portuguese nationalists, British imperialists or South African revisionists.

I’ve dealt with all this in my book Knot of Stone (2011) which, alas, appeared before the publication of Johnson’s paper. Here I show how one version may present Almeida as a victim while another casts him as a hero. For instance, Camões says Almeida was a victim of fate and predestination; Ian Colvin says he and his men fought with valour; while Victor de Kock says they fled like cowards. For one it is Almeida’s personal tragedy, for another it is the Cape’s geo-political destiny. While each version may emphasize unique aspects of the tragedy, it still remains one and the same story. My book’s main character, Sonja Haas, concludes: “Each told what he wanted recorded for prosperity. It was a mix of archival research and bardic inspiration, personal opinion and public information. Inseparable, like mud and manure.” And like the four Gospel versions of Christ’s crucifixion, these are not only inconsistent but also seriously incomplete, each with their own emphasis, resonance, or bias if you like, but they still remain the same Easter story. So I don’t think it quite right to talk about “the Almeida stories” in the plural. The plurality lies in the ever-changing meanings given to one overall story.

PTM: As the first Portuguese Viceroy in India, he was both arrogant and aggressive. He had achieved fame as a conqueror of the Moors at Granada in Spain, and of the African coastal towns of Kilwa and Mombasa. He was known to have burned and pillaged his way through Africa, India and Indonesia. Almeida was the great Portuguese conqueror who wreaked havoc across the world but was brought down by a small clan of Khoe people whose kindness he repaid with treachery.

NV: I’m afraid such generalised character descriptions of Almeida are both inaccurate and misleading. Almeida was not the mighty conqueror, great or cruel, that many sources make him out to be. As far as I know, he only touched the coasts of East Africa and West India—never venturing inland himself—and certainly never reached Indonesia? Having said this, I admit it was an era of religious wars and that colonialists would, over the next four-and-a-half centuries, impose a culture of violence on those they conquered, converted or tried to civilise. However, Almeida actively opposed the violence and destruction that came with warfare: in Kilwa he placed his son at the doors of Imir Ibrahim’s palace to prevent his men from looting and, after they sacked Mombasa, kept only a single spear as his own personal memento.

NV: I’m afraid such generalised character descriptions of Almeida are both inaccurate and misleading. Almeida was not the mighty conqueror, great or cruel, that many sources make him out to be. As far as I know, he only touched the coasts of East Africa and West India—never venturing inland himself—and certainly never reached Indonesia? Having said this, I admit it was an era of religious wars and that colonialists would, over the next four-and-a-half centuries, impose a culture of violence on those they conquered, converted or tried to civilise. However, Almeida actively opposed the violence and destruction that came with warfare: in Kilwa he placed his son at the doors of Imir Ibrahim’s palace to prevent his men from looting and, after they sacked Mombasa, kept only a single spear as his own personal memento.

For what it’s worth, Almeida openly criticised King Manuel’s heedless desire for territorial possessions in Africa and India (then common practice among both Christians and Muslims) and argued for command of the open sea instead. Almeida’s so-called Blue Sea policy was the cause of his downfall as Viceroy and, partly, the reason behind his possible assassination at the Cape. It seems clear to me that we should separate the actions of Almeida and those loyal to him—most of whom were left dead on the beach that Friday—from the conspirators who I now believe instigated his demise. Ironically, both Almeida and the Khoena may have been victims of deception and betrayal that day.

PTM: I stand corrected about Indonesia. Almeida’s only ‘conquest’ in Indonesia was by way of means of a treaty signed with Melaku (Malaysia). His focus was aggression up the East Coast of India (Malabar) and Bengal. The battle of the Bay of Diu was one of the most important and bloodiest of naval battles in history, and was led by Almeida against the Egyptians and Indians. In character Viceroy D’Almeida is said to have had his fleet sail along the coast firing the arms and legs of prisoners out of cannon and onto the roofs and streets of native towns. Hardly the actions of the character you describe. When one talks of Africa of this time and talks about Portugal’s military exploits and dominance it is generally understood that one is referring to North Africa, West Africa and then Sofala, Kilwa, Mombasa and Zanzibar. In all of these areas Almeida has a recorded bloody history regardless of the odd anecdote of compassion. He was not ‘touching on’ the coast of East Africa in my understanding, notwithstanding that there were forces at the time who had a very different agenda more associated with earlier epochs of acquiring possessions rather than opening corridors of trade in keeping with the new commercialism that was emerging. The Portuguese writers who do not agree don’t attempt to suggest that Almeida was less violent in battle than his contemporaries.

NV: The ghastly account of severed arms and legs is abhorrent, certainly, and I don’t defend such action. But do you know the place or the people involved? Was it off the coast of India or Africa? Was it Almeida or Albuquerque or Gama? I raise the question not in denial, but to suggest that these may be stock images in the historical record. The same convention (or licence) is found in the art, poetry and cartography of that period.

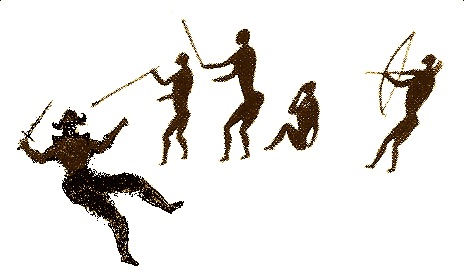

View of Aden (top), Mombasa (bottom left), Kilwa (centre) and Sofala (right) by Georg Braun and Abraham Hoegenberg, 1572-1624. During an era of overseas expansion when territories had to be fought for, coastal towns were viewed from the safety of the roadstead. Likewise at the Cape, settlements along Europe’s new trade route were recognized by their tokens of civilization: a fort, church, hospital and sheltered anchorage. As these drawings tended to be generic, and interchangeable, they would often be confused by later writers.

View of Aden (top), Mombasa (bottom left), Kilwa (centre) and Sofala (right) by Georg Braun and Abraham Hoegenberg, 1572-1624. During an era of overseas expansion when territories had to be fought for, coastal towns were viewed from the safety of the roadstead. Likewise at the Cape, settlements along Europe’s new trade route were recognized by their tokens of civilization: a fort, church, hospital and sheltered anchorage. As these drawings tended to be generic, and interchangeable, they would often be confused by later writers.

After Aristotle, classical historians believed it was their duty to ennoble the world through art and poetry, and this assumption influenced how Western history would be written for the next two millennia—right up to the early twentieth century. Remember, Aristotle’s Poetics argues that poetry expresses our highest human values; whereas history only tells us what we once were and not what we may yet become. As a result, Camões and his contemporaries wrote for the purpose of improving the moral marrow of the Portuguese people. Their writings were supposed to teach by way of good examples, but as Portugal’s past included such sullied episodes, they had to recast these to support the assumption of a divine historical purpose. They thus welded fact and ideals to embolden their nation. I don’t believe Knot of Stone belongs to this camp, nor does it bear a torch for any other.

PTM: While I respect your version of history and its groundbreaking approach, it still entrenches a dominant European interpretation of events regardless of local experiences. But saying this is not meant to invalidate your story. I personally find an elaborate plot complete with pre-modernist intrigues and esoteric themes embracing the real and spirit worlds and secret societies a wonderful and captivating approach… but I cannot accept it as the authorative version. There never will be an authorative version. Historical ‘truth’ is an illusion.

NV: I don’t make such claims either. I accept that there’s no indisputable truth, only the truths we choose to believe in. Or, as one of my characters says: “To speak the truth does not assert anything significant about the world, but merely indicates that there is a general agreement about its nature, which we then accept as true.” Like you, I also know that our assertions about the past are biased.

PTM: All versions have their bias. My interest in early Cape roots has one too. For many years ‘Coloured’ people have been ridiculed and told that they, or rather we, are a bastard people with no history or heritage. For the first time we have the chance to explore. We are only just discovering what was hidden from us during the Colonial period; including Apartheid manipulations of our history. At first it may seem that this is a serious disadvantage because we don’t have the array of materials that were available to others for the past millennia.  But our advantage is that we see things with different eyes and look with less cluttered minds. We are just opening ourselves up to new horizons, to new political vistas. Our focus too is on ourselves and the ancestry that we are intimately bound up with. We must adjust the lens ourselves. It’s our turn to gaze back.

But our advantage is that we see things with different eyes and look with less cluttered minds. We are just opening ourselves up to new horizons, to new political vistas. Our focus too is on ourselves and the ancestry that we are intimately bound up with. We must adjust the lens ourselves. It’s our turn to gaze back.

NV: Which is why you dislike the Eurocentric gaze and ‘white’ revisions of your history?

PTM: Yes. The European lens has dominated our lives and so, naturally, we have to part company with it for a while. While we do so, the European lens will naturally change focus and become excited with its own discoveries—but this is not where we are at right now. We need to revise our own history.

Part Two of this discussion continues here.

Nicolaas Vergunst

Idiots… they came to loot India… some people still worshipping those bloody P’gueses.

Ironically, Rajesh, Almeida was killed for the loot his masters wanted from Arabia and Moorish Granada, not India. His refusal to submit these gifts cost him his life…

Dear Patric and Nicolaas

I am impressed by your discussion of Almeida’s fate and how you each highlight contradictory aspects to his character—and in the historical record. I note that you’re not alone in this as other authors have addressed the matter recently too. It clearly is time to rethink this saga and, if possible, to integrate some differing points of view—including the old versions. As a Dutch researcher-educator with a background in European cultural history, I’d like to contribute to your discussion.

For me the most important ‘new’ commentator has been Walter Johannes Stein (1891–1957), a historian and economist, who spent his latter years researching Almeida’s unusual dual nature. On the one hand he saw Almeida as a mercurial Grail knight following a spiritual impulse and, on the other, as a fierce Mars-like warrior pusuing a crusade. Stein came to the conclusion that Almeida had, after an inner crisis in 1492, transformed from a soldier defending his own faith to one ushering in a new world order. Almeida realised, Stein says, that an era of world wide commerce had begun and that his successors, particularly the British, would use Portugal’s foundations for a modern global economy. Walter Johannes Stein published these ideas in his magazine The Present Age, now available online.

Thanks for your comment, Frans, and for the reference to Walter Johannes Stein. Yes, it seems a good time to reappraise the received histories of this event and to rehabilitate its victims—including Almeida. I say this not to diminish the Khoena, who were both victims and victors, but to (re-)emphasise that Almeida lost both his life and his reputation that day. As João de Barros, one of the ‘old’ chroniclers, wrote in his dedication to Almeida: “It is more important to acquire a good name than an estate, because the name is eternal property.” (Década II, 1552)

As Patric also knows, I’ve tracked this saga for over thirty years, ever since I first heard about an alternative narrative in the early 1980s, and gradually managed to trace it back to an intimate circle of friends in Cape Town around 1960. Strangely, many of them were also Dutch educators and given your comments, significantly, drew their inspiration from Walter Johannes Stein. This is all in Knot of Stone, including discussions with individuals still alive today or, at least, with those able to remember things with a measure of clarity and consistency. Most now have so-called senior moments when I speak to them. So it’s a slow step-by-step process, as you can well imagine.

I hope to post an interview soon. For now, at least, there’s a comment by one of the original Dutch members, Eva Picard. See under Reviews. Thank you, again!

Hey there, I’ve been reading your website for a long time now and finally got up the courage to give you a shout from Austin Texas! I just want to know why you chose the name Sonja for your main character? Keep up the fantastic posts!

I’m delighted you dropped by, Sonja, assuming you’re the same Austin Texan who regularly visits our website? We’ve often wondered who’s out there, reading our posts at all hours of the morning, when most sensible Americans are still asleep?

Why choose the name Sonja? As a restless Dutch historian, she counterbalances her travelling partner, Jason, a sceptical Afrikaans archaeologist. Their search for the truth, for the historical facts surrounding Almeida’s murder, leads each to an individual conclusion. It’s a journey of self-discovery wherein Sonja finds herself challenged by new beliefs and ideas while Jason, instead, seeks confirmation in a scientific world. Their entangeld relationship is revealed by the simple anagram: S O N J A = J A S O N

What a wonderful resource, Nicolaas, thanks. Knot of Stone seems to be enjoying much popularity. A great achievement!