The 1510 massacre of Francisco d’Almeida and his sixty compatriots was, until recently, seen as “one of the greatest tragedies in the history of Portugal”.1 Yet today the event receives scant attention since most historians are quick to overlook it, journalists tend to dismiss it, and the public have all but forgotten it. If and when the tragedy is mentioned, it invariably serves two ulterior motives. First, to demonstrate all the violent dangers faced by the early explorers: “Hottentots stove in Almeida’s head on some obscure South African beach.”2 Or, secondly, to show that Almeida had to pay for his arrogance.3 Indeed, for the last five centuries, no one ever stopped to question the event—or the historical records? Moreover, to commemorate its fifth-centenary, the entire saga was framed as South Africa’s first racial confrontation.4

The 1510 massacre of Francisco d’Almeida and his sixty compatriots was, until recently, seen as “one of the greatest tragedies in the history of Portugal”.1 Yet today the event receives scant attention since most historians are quick to overlook it, journalists tend to dismiss it, and the public have all but forgotten it. If and when the tragedy is mentioned, it invariably serves two ulterior motives. First, to demonstrate all the violent dangers faced by the early explorers: “Hottentots stove in Almeida’s head on some obscure South African beach.”2 Or, secondly, to show that Almeida had to pay for his arrogance.3 Indeed, for the last five centuries, no one ever stopped to question the event—or the historical records? Moreover, to commemorate its fifth-centenary, the entire saga was framed as South Africa’s first racial confrontation.4

Ironically, the Portuguese themselves propagated this tragedy as an act of retribution: “The Cape of Storms shall be his hasty, final tomb. Those killed by him will measure out his just doom.”5

Whichever way one wants to frame it, one fact remains: Portugal never colonised the Cape. “This brush with the Hottentots in 1510 decided the fate of South Africa, which would probably [certainly?] have been a Portuguese colony. As it was, thereafter, the Portuguese avoided the Cape and refuelled on the west or east coast, settling at Angola and Mozambique instead.”6

Whichever way one wants to frame it, one fact remains: Portugal never colonised the Cape. “This brush with the Hottentots in 1510 decided the fate of South Africa, which would probably [certainly?] have been a Portuguese colony. As it was, thereafter, the Portuguese avoided the Cape and refuelled on the west or east coast, settling at Angola and Mozambique instead.”6

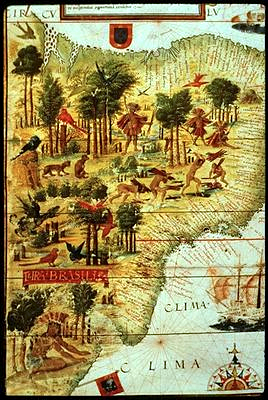

Portugal could thus have controlled the entire African sub-continent, from the mouth of the Congo River to the Mozambique Channel, and for the next four hundred and fifty years—that is, until the mid-1970s, making of southern Africa a second Brazil. Potentially.

I have no doubt that the history of South Africa and the destiny of its inhabitants would have followed a different course—but for this tragic event. We need only glance back to see how different the circumstances were after South Africa submitted to the influence of pragmatic Dutch Protestants, displaced French Huguenots (themselves anti-Catholic) and entrepreneurial English industrialists. The sudden discovery of diamonds and gold in the late 1800s helped to consolidate Britain’s colonial possessions and was used to bolster the British Commonwealth. Had it, instead, been a Portuguese colony, all its wealth would have been drained curbing a crisis of mass emigration and bankruptcy in Lisbon.

I have no doubt that the history of South Africa and the destiny of its inhabitants would have followed a different course—but for this tragic event. We need only glance back to see how different the circumstances were after South Africa submitted to the influence of pragmatic Dutch Protestants, displaced French Huguenots (themselves anti-Catholic) and entrepreneurial English industrialists. The sudden discovery of diamonds and gold in the late 1800s helped to consolidate Britain’s colonial possessions and was used to bolster the British Commonwealth. Had it, instead, been a Portuguese colony, all its wealth would have been drained curbing a crisis of mass emigration and bankruptcy in Lisbon.

The origin of the name Brazil remains uncertain and could mean either “land of the palm trees” or, after the brazilwood, “red like an ember”. Neither of which grew at the Cape.

1. Victor de Kock, By Strength of Heart, 1953:28.

2. Ronald Fritze, The Great Voyages of Discovery 1400–1600, 2002:239.

3. Andrew Smith & Roy Pheiffer, The Khoekhoe at the Cape of Good Hope: seventeenth-century drawings in the South African Library, 1993:11.

4. Iziko Museums, 5oo-year Commemoration Symposium of the 1510 Khoi-Almeida Confrontation, press release, 25 September 2010.

5. Luís de Camões, The Lusíads, 1572, Canto 5:45.

6. Jose Burman, Safe to the Sea, 1962:15.

Nicolaas Vergunst

What would have happened if Almeida’s visit ended in friendship? I hope your research will give us an answer, and that your book finds its way to readers all over the world. It is an important story and part of our world history.

Had the Portuguese stayed, who knows, there’d be a large statue of Christ the Redeemer on top of Table Mountain, Rio-like, and Desmond Tutu may have become the first black Pope.

This piece was cogent, well-written and pithy.