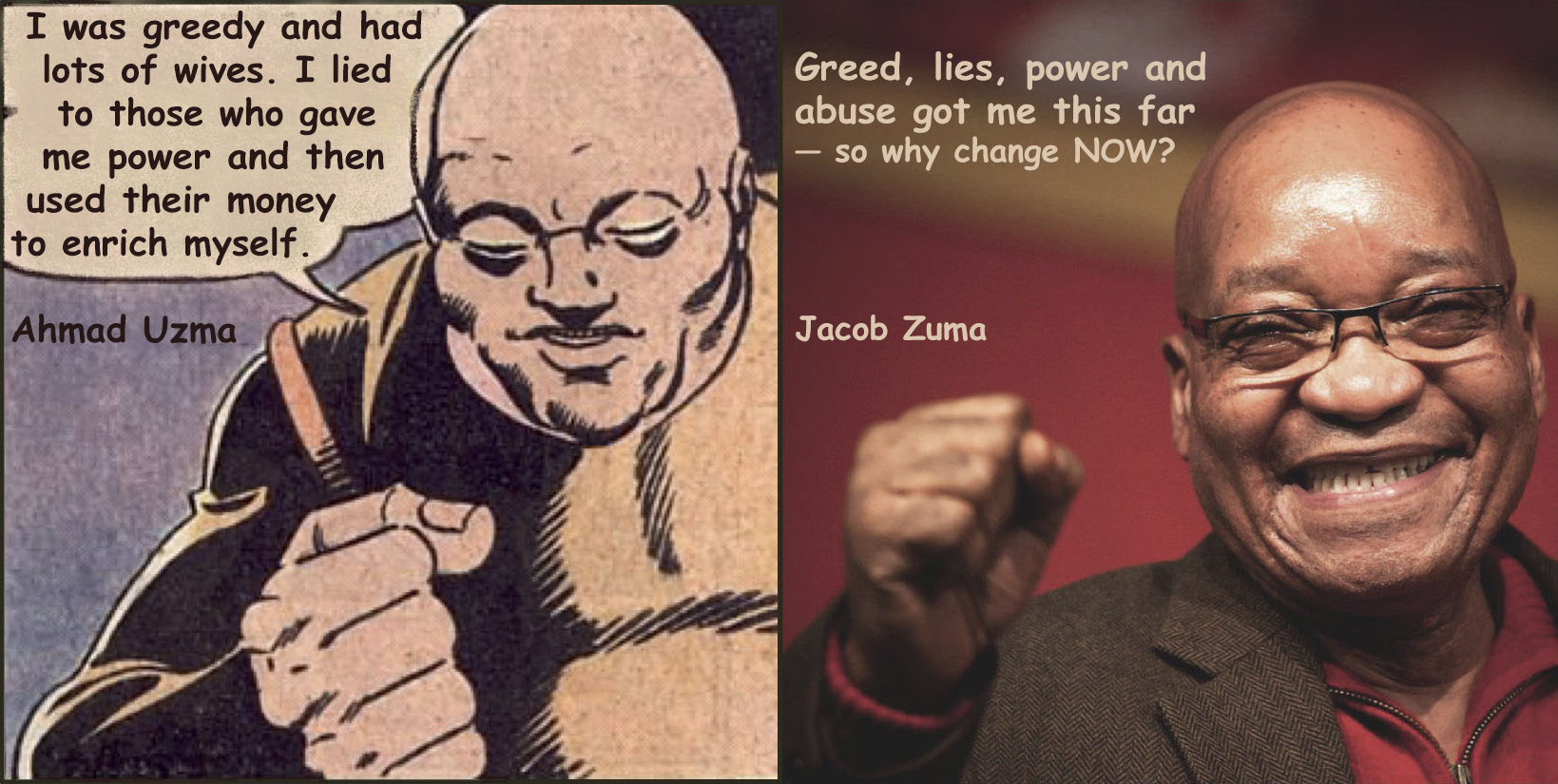

Among the most startling and unprecedented revelations in Knot of Stone are those about Jacob Zuma’s alleged past lives—including his greed, corruption and intransigence. These were conveyed by a local clairaudient Laurence Oliver in 2009 (two years prior to publication of KoS) and suggest that all Zuma owns will be seized and all his deeds undone (see Chapters 94-95). Here follows a brief summary.

Among the most startling and unprecedented revelations in Knot of Stone are those about Jacob Zuma’s alleged past lives—including his greed, corruption and intransigence. These were conveyed by a local clairaudient Laurence Oliver in 2009 (two years prior to publication of KoS) and suggest that all Zuma owns will be seized and all his deeds undone (see Chapters 94-95). Here follows a brief summary.

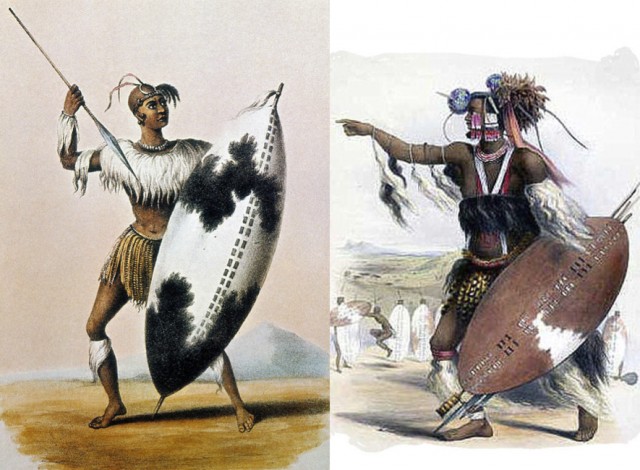

Clockwise from Left to Right: Shaka Zulu, king of the Zulu; Warrior Utimuni, a nephew of Shaka; and Jacob Zuma. President Zuma is shown performing a traditional Zulu dance at the wedding to his fourth wife at his home in KwaZulu-Natal, 2008. Reuters.

“Attila the Hun, Julius Caesar, Napoleon, Hitler and Shaka Zulu all suffered miserable lonely deaths.” Credo Mutwa, KoS p.78

Jacob Msimbiti, a convicted amaXhosa cattle thief and escapee from Robben Island, was present at Shaka Zulu’s death at kwaBulawayo in 1828. Msimbiti had arrived at the royal kraal four years before and, on hearing of his daring journey, including that he had twice survived a capsized boat, Shaka nicknamed him Hlambamanzi (the “Swimmer”) and retained him as his aide, adviser and interpreter. Alas, Msimbiti would go on to betray Shaka and Dingane. According to Dr Oliver, this intransigent soul was unable to rise above his past:

Jacob Msimbiti

After his tragic life as Montezuma, his soul ached with a deep distrust and hatred of white men. This carried over into his next life, recorded in the amaZulu chronicles of Shaka and Dingane, under the name Jacob.Jakob or Jacob was the Christian name given to him by Dutch settlers and British soldiers, as being phonetically close to his isiXhosa name, Jakoet. His clan name was Msimbiti.

Convicted of cattle theft on the Colony’s eastern frontier, Jacob was sent to the penal colony on Robben Island in 1819, along with the banished amaXhosa king Makhanda (hence the name “isle of Makhanda”). Jacob and several others were involved in the daring escape of 1820—in which Makhanda, tragically, drowned when their boat capsized—and Jacob himself was caught and sentenced to hard labour in irons for a further fourteen years. However, Jacob was released soon after into the service of English mercantile traders. They needed an interpreter.

On a sea-going expedition with his new masters, including the notorious ex-lieutenant Francis Farewell, their boat floundered in the surf off St Lucia. Jacob rescued one of his masters from drowning. Nevertheless, he was blamed for toppling the boat, at which he deserted and swiftly fled into the bush. Farewell and others would later catch up and seal his fate.

For now, Jacob arrived at the royal kraal of Shaka Zulu who, on hearing his woeful tale, nicknamed him Hlambamanzi, the “Swimmer”, and retained him as his personal aide, adviser and interpreter. While king Shaka welcomed white traders, Jacob always warned against their treachery.

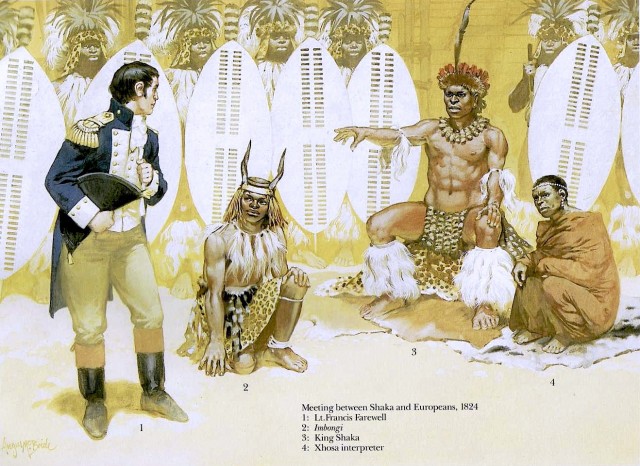

‘Meeting between Shaka and Europeans, 1824′ by Angus McBride, 1989. Here Farewell greets the Zulu king in the company of a praise-poet (n0. 2) and a Xhosa interpreter (no. 4). The latter could be Jacob Msimbiti who, according to Dr Oliver, reached the kraal before his masters. The artist also depicted Almeida’s tragic death, a keystone image in KoS (p.70).

‘Meeting between Shaka and Europeans, 1824′ by Angus McBride, 1989. Here Farewell greets the Zulu king in the company of a praise-poet (n0. 2) and a Xhosa interpreter (no. 4). The latter could be Jacob Msimbiti who, according to Dr Oliver, reached the kraal before his masters. The artist also depicted Almeida’s tragic death, a keystone image in KoS (p.70).

It would seem that Jacob eventually switched his allegiance to Shaka’s half-brother, Dingane, for when the latter assassinated the king it was Jacob who sent foot messengers to the traders, saying they had nothing to fear as the new king invited them to trade skins and ivory. Acting as Dingane’s ambassador, Jacob promised them renewed peace and prosperity in Zululand.His former masters were suspicious, however, as Jacob had openly opposed the presence of white hunter-traders in Natal under Shaka’s rule. The English were also wary of his criminal record and widespread reputation as a liar and schemer, even among his compatriots.

And indeed it was that Jacob constantly urged Dingane to avoid association with the Whites. He schemed and plotted, calling them “evil sorcerers” while poisoning the king’s mind with lurid tales of their cruelty and treachery.

He was again arrested by the Whites for pilfering, and they pressed Dingane to put him on trial for deceit and duplicitous conduct. Dingane vacillated, half-believing Jacob’s insistent claim that the Dutch and British were conspiring to invade and steal his kingdom.

But, after Jacob was caught stealing again from the royal herd, Dingane lost his temper and ordered his execution. Jacob was hunted down by his arch-rival, John Cane, to whom Dingane later gave eighty cows from Jacob’s own herd.

Dingane never forgot Jacob’s oft-repeated prophecy—echoing Shaka’s dying words—that one day the Whites would conquer and rule the land. It was his past experience as Montezuma that told him so. And surely he was right?

Clairaudient message cited in KoS pp.428-429

We should not despair over South Africa’s future, says Dr Oliver, since we all have to prove ourselves again in other lives. So too for president Jacob Zuma, should he wish to contribute positively to the lives of Msimbiti and Montezuma. The historical portrayal of Montezuma II (c.1466–1520) has been largely coloured by his role as ruler of a defeated nation, and several sources describe him as weak-willed and indecisive. Such biased reportage makes it difficult for us to understand his motives and actions today, a problem Zuma seems to be bedeviled with too.

Feathered headdress of Montezuma, unauthenticated, courtesy of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. According to Dr Oliver, the karmic history of Jacob Msimbiti and Jacob Zuma are linked to Montezuma II.

Feathered headdress of Montezuma, unauthenticated, courtesy of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. According to Dr Oliver, the karmic history of Jacob Msimbiti and Jacob Zuma are linked to Montezuma II.

Montezuma II, emperor of the Aztecs, by George Stuart (left); Charles Ricketts, The Death of Montezuma, c.1927 (right). Courtesy South African National Gallery, Cape Town.

Montezuma II, emperor of the Aztecs, by George Stuart (left); Charles Ricketts, The Death of Montezuma, c.1927 (right). Courtesy South African National Gallery, Cape Town.

Montezuma

The historical Montezuma was the last Aztec emperor of Mexico. His initial career was as a military leader and priest in the temple of the war god, Huitzilopochtli. In accordance with Aztec custom his coronation was accompanied by mass human sacrifices. As an expansionist, he enlarged his empire through the conquest of the Honduras and Nicaragua. His rule was accompanied by unfavourable omens—notably the predicted return of Quetzalcoatl, a local god, white in colour.The arrival of Cortés and the Spaniards was thought to fulfil this prophecy and so Montezuma, with uncharacteristic diplomacy, did not react aggressively. In return, he was imprisoned by Cortés in Mexico City, precipitating an uprising by his brother and heir. In an effort to divert the revolt, Cortés induced Montezuma to address his people from the Spanish stronghold. The angry mob responded by showering Montezuma with stones and arrows, and so he died, either by wounds inflicted by the mob or, afterwards, at the hands of his captors. We must wait to see how he redeems himself in South Africa.

Clairaudient message cited in KoS p.427

Further back in history, Zuma is alleged to have been an official in Kublai Khan’s court.

Ahmad Uzma

From his name, Ahmad Uzma, it would appear that he was of Arabic descent and came from Uz, a Turkic region now called Uzbekistan. Uzma rose to the position of finance minister, taking advantage of his master’s misplaced trust and the distractions of civil war. He was reputedly the most corrupt court official and renowned for his many wives. Though he was accused of murder, the Grand Khan sidelined all attempts to impeach him and kept him at court. Despite this, Uzma’s abuses of power did not stop—nor did his lucrative exploitation of war against the Kublai’s brother—since he also faced similar charges for capitalizing on arms-deals. Uzma’s story was apparently known to Marco Polo.Uzma disposed of his rivals and critics in ruthless ways. Some were demoted or imprisoned, many were executed, others simply vanished. However, he surrounded himself with cronies until he was ambushed and killed by a zealous military commander, Wang Zhu, and several co-conspirators. Kublai had the ring-leaders executed. Before he was beheaded, Wang Zhu cried out: “I, Wang Zhu, die for having rid the world of a pest!” Uzma received a state funeral, but when Kublai finally came to learn the truth about him, he exclaimed: “Wang Zhu was perfectly right to kill Uzma!” Everything Uzma owned was seized. Everything he had done was undone.

Paraphrased clairaudient message from KoS p.426

Can the besieged soul of Montezuma-Msimbiti redeem himself? To do so, Zuma will have to overcome the arrogance and fears of his past lives, including the power-hungry money-grabbing Uzma, and follow the example of his predecessor Nelson Mandela. While the past lives of Mandela and his circle are explored in another post, may it suffice to conclude here that Zuma was also a part of this ring in ancient Egypt.

The bond between Ramaphosa and Zuma can be traced back to ancient Egypt, c.1300BCE, when they served as rival Amenite priests.

The bond between Ramaphosa and Zuma can be traced back to ancient Egypt, c.1300BCE, when they served as rival Amenite priests.

Usermontu

[Jacob Zuma] was an Amenite priest called Ahmose or Ahmes and partisan to Nefertiti’s plot to install the abducted Tutankhaton as a puppet pharaoh. With their success he became vizier of the South at Thebes under Tutankhamen, and is remembered as Usermontu.More importantly, the vizier of the North was Pa-Ramose [Cyril Ramaphosa] who played a counterbalancing role at Memphis.

Paraphrased clairaudient message from KoS p.425

While loyal to the same religio-political order, Pa-Ramose and Usermontu were themselves rivals. Pa-Ramose played a decisive role in the struggle for stability between the 18th–19th dynasties. Pharaoh Horemheb [Nelson Mandela] chose Pa-Ramose [Ramaphosa] to be his successor in return for his loyalty to the throne, and because he himself was childless. Pa-Ramose had a son and grandson and could thus secure a royal succession. Pa-Ramose became the first pharaoh of the next age, the nineteenth dynasty, and is known to us as Ramses I.

If what happened then is anything to go by, Ramaphosa will usher in an era that reaches new heights. We shall watch what happens between these age-old rivals in the not too distant future.

Nicolaas Vergunst

Angus McBride’s picture of Shaka with the Xhosa interpreter is truly remarkable! How could he have imagined such an accurate scenario and, more importantly for your book, could he have known the translator was Jacob Msimbiti? If so, where on earth did he get his information from?

Your posts are superb—I hope the right people get to read them.

McBride may have known about Jacob Msimbiti via an interesting passage given in Adam Hochschild’s The Mirror at Midnight: A South African Journey, 1990. As McBride’s illustration was published in 1989, a year before Hochschild’s account, they may have relied on the same source for their information, probably one by the acclaimed Zulu military historian Sighart “SB” Bourquin (1915-2004). Despite this, Hochschild’s biographical synopsis of Jakot Msimbiti is well worth reading here.

Montezuma’s feathered headdress to stay in Vienna, for now, says latest report: Verentooi Montezuma blijft in Wenen.

Could it really be the big Ms headdress or a later artifact?

Although rare and unique, its authenticity is uncertain as no historical documents link it to Montezuma or, for that matter, to any other Aztec ruler. Moreover, it is not known if the headdress was ever worn, officially or otherwise, nor by whom.

The provenance of exotic curiosities were often forgotten or, simply, incorrectly registered; such as the Brazilian axe in Vienna that was (similarly) attributed to “Montezuma II, Inca of Mexico”.

For more info on feathered imports and how they found their way to Vienna, see Vienna’s Mesoamerican Featherworks.